Bhakti Movement and Sufi Movement PPT Download

Contents

- 1 Bhakti Movement and Sufi Movement PPT Download

- 2 UPSC Prelims PPT Bundle Product Details

- 3 (BUY ONLINE)

- 3.1 Check Price & Buy (Redirects to Pricing Page)

- 3.2 What is Bhakti movement?

- 3.3 Bhakti Movement: Embracing Love and Equality Through Devotion

- 3.4 Alvars and Nayanars: Pioneering Saints of the Tamil Bhakti Movement

- 3.5 Basavanna: Pioneer of Lingayatism and Social Reformer

- 3.6 Bhakti Blossoms in Maharashtra: The Varkari Tradition

- 3.7 Kabir: The Universal Bhakti Poet

- 3.8 Nanak: The Visionary Guru

- 3.9 Ravi Das: A Voice of Equality and Social Justice

- 3.10 Vaishnavite Movement: Devotion and Humanism

- 3.11 What is Sufi movement?

- 3.12 The Emergence of Sufi Mysticism

- 3.13 Sufism’s Early Presence in India

- 3.14 Chishti Silsilah: Spreading the Light of Devotion

- 3.15 Suhrawardi Silsilah: Embracing State Connections

- 3.16 Firdawsi Silsilah in India

- 3.17 Shattari Silsilah in India

- 3.18 Qadiri Silsilah: Sufi Tradition in India

- 3.19 Naqshbandi Silsilah: Upholding Orthodoxy in India

- 3.20 Bhakti Philosophies in Medieval India

- 3.21 Advaita by Sankaracharya: Unraveling the Essence of Oneness

- 3.22 Vishistadvaita of Ramanujacharya

- 3.23 Sivadvaita of Srikanthacharya

- 3.24 Impact of the Bhakti-Sufi Movements on Indian Society

- 3.25 Table: Philosophical schools

- 3.26 Table: Difference Between Bhakti and Sufi Movements

Bhakti Movement and Sufi Movement PPT Download, In the rich tapestry of India’s religious history, two profound and transformative movements emerged during medieval times – the Bhakti Movement and the Sufi Movement. Rooted in distinct religious traditions, these movements left an indelible mark on the fabric of society, fostering devotion, love, and mysticism. Although originating from different contexts, these movements shared common ground in their pursuit of spiritual enlightenment and a deeper connection with the divine.

Bhakti Movement and Sufi Movement PPT Download

(Lec – 5)

UPSC Prelims PPT Bundle Product Details

(BUY ONLINE)

| Placement / Section | Details / Click To Action Text |

|---|---|

| Title | UPSC Prelims PPT Notes (BUNDLE) |

| Number of PPTs / Slides | 160+ PPTs |

| Delivery Method | Instant Access after Payment (Google Drive Folder) |

| Additional Info | Full UPSC Prelims Coverage, Study-Friendly PPT Format |

| Copyright / Ownership | Self-made Notes (slideshareppt.net) |

| Payment | Online Gateway – QR, CREDIT CARD, UPI etc… |

| Pricing / Purchase CTA | Check Price & Buy (Redirects to Pricing Page) |

| Demo Link | View Sample Slides (Click to Open Demo) |

What is Bhakti movement?

The Bhakti Movement was a socio-religious reform movement that emerged in medieval India, roughly between the 7th and 17th centuries. “Bhakti” translates to “devotion” in English, and the movement was characterized by intense devotion and love for a personal god. Unlike the rituals and complex religious practices of the time, the Bhakti Movement emphasized a direct, emotional connection between the devotee and the divine, advocating for a more accessible and personal approach to spirituality.

Key Characteristics of the Bhakti Movement:

- Personal Devotion: Bhakti emphasized a deep, personal, and emotional connection with a chosen deity, such as Vishnu, Shiva, or the Goddess Devi. Devotees believed in a loving relationship with the divine, transcending formalities.

- Rejection of Caste and Social Barriers: Bhakti saints and proponents rejected the rigid caste system and societal hierarchies. They emphasized that devotion to God was open to everyone, regardless of their caste, gender, or social status.

- Use of Vernacular Languages: Bhakti saints composed devotional poetry and songs in regional languages, making religious texts and teachings accessible to common people who didn’t understand classical Sanskrit. This widespread use of vernacular languages facilitated the spread of Bhakti ideas.

- Equality and Social Reform: Bhakti saints challenged social injustices and advocated for equality. They condemned practices like untouchability, sati (the immolation of widows), and advocated for women’s rights, encouraging women to actively participate in religious gatherings.

Example of Bhakti Movement – Sant Tulsidas and his Rama Bhakti:

One notable example of the Bhakti Movement is the life and work of Sant Tulsidas. He was a 16th-century saint and poet in India, best known for his epic poem, the Ramcharitmanas. This work, written in Awadhi, a regional dialect, is a retelling of the ancient Hindu epic, the Ramayana, focusing on the life and teachings of Lord Rama.

Tulsidas’ devotion to Lord Rama exemplifies the core ideals of the Bhakti Movement. Through his poetry, he emphasized the importance of unwavering devotion and love for Lord Rama, highlighting Rama as an embodiment of dharma (righteousness) and compassion. Tulsidas’ writings not only spread the message of devotion but also played a crucial role in promoting the use of vernacular languages for religious expression.

The Bhakti Movement, through figures like Sant Tulsidas, left an indelible mark on Indian spirituality, fostering a culture of love, inclusivity, and devotion that continues to influence religious practices and beliefs in modern India.

Bhakti Movement: Embracing Love and Equality Through Devotion

Regional Roots and Language Diversity:

- The Bhakti movement, a transformative wave of spirituality and social reform, first blossomed in Tamil Nadu during the period spanning the seventh to twelfth centuries. This profound transformation found its voice in the heartfelt verses of the Nayanars, devotees of Shiva, and the Alvars, devotees of Vishnu. Contrary to the cold formalities of traditional worship, these saints envisioned religion as a warm, loving bond between the worshipper and the worshipped. To reach a broader audience, they chose to express their devotion in the vernacular languages of the region, namely Tamil and Telugu. This linguistic choice was pivotal, enabling the movement to resonate deeply with people from diverse backgrounds.

Spread and Adaptation: The Power of Local Languages

- Over time, the Bhakti ideals trickled from the southern heartland to the northern regions, albeit at a gradual pace. Sanskrit, the longstanding vehicle of thought, underwent a transformation. Notably, the Bhagavata Purana, dating back to the ninth century, departed from traditional Puranic forms. Focused on Krishna’s childhood and youth, this work ingeniously used Krishna’s adventures to elucidate profound philosophies in simple, relatable terms. This departure marked a turning point for the Vaishnavite movement, an integral facet of the Bhakti movement. A key strategy employed in disseminating Bhakti ideology was the use of local languages. Bhakti saints crafted their verses in regional tongues and translated Sanskrit texts, ensuring the accessibility of profound spiritual teachings to a wider audience. This linguistic diversification included luminaries like Jnanadeva in Marathi, Kabir, Surdas, and Tulsidas in Hindi, and Chaitanya and Chandidas in Bengali, amplifying the reach of Bhakti thoughts across the vast tapestry of India.

Egalitarianism and Social Reform: Shaping a Just Society

- At the core of the Bhakti movement was the belief in universal salvation, transcending the divisive barriers of caste, creed, or religion. The Bhakti saints, themselves hailing from diverse social strata, exemplified this egalitarian ethos. Ramananda, who welcomed disciples from both Hindu and Muslim backgrounds, emerged from a conservative Brahmin lineage. Kabir, a weaver by trade, and Guru Nanak, the son of a village accountant, reinforced the movement’s inclusive spirit. These saints vehemently denounced the caste system, advocating for social reforms. Their courage extended beyond religious realms; they actively opposed practices such as sati (the immolation of widows) and female infanticide, advocating for women’s rights and encouraging their active participation in religious ceremonies.

Sectarian Harmony: A Unifying Vision

- In this tapestry of Bhakti saints, the contributions of Kabir and Guru Nanak stand out prominently. Drawing wisdom from both Hindu and Islamic traditions, these luminaries aimed to bridge the gulf between Hindus and Muslims. Their teachings, grounded in love and devotion, sought to foster understanding and harmony between these communities. By embracing the rich tapestry of regional languages, advocating for social equality, and nurturing a spirit of inclusivity, the Bhakti movement not only reshaped the religious landscape of medieval India but also sowed the seeds for a more compassionate and united society, leaving a profound legacy that endures through the ages.

Table: Key Aspects of the Bhakti Movement in India

Here is the information presented in the form of a table for better visualization:

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Origin and Region | The Bhakti movement originated in Tamil Nadu between the 7th and 12th centuries and gradually spread from South India to North India. |

| Devotees and Deities | Emotional poems of Nayanars (devotees of Shiva) and Alvars (devotees of Vishnu) expressed religion as a loving bond between worshipped and worshipper. |

| Language and Accessibility | Bhakti saints composed verses in local languages such as Tamil, Telugu, Marathi, Hindi, Assamese, Bengali, Rajasthani, and others, making teachings accessible to the masses. |

| Sanskrit Transformation | Sanskrit texts like the Bhagavata Purana were transformed, explaining deep philosophy through Krishna’s exploits in simple language, marking a significant Vaishnavite moment. |

| Inclusivity and Equality | Bhakti saints believed in universal salvation, rejecting distinctions of caste, creed, or religion. Saints like Ramananda, Kabir, Guru Nanak, and Namdev came from diverse backgrounds. |

| Social Reforms | Bhakti saints opposed caste system, institutionalized religion, and social injustices. They advocated social reforms, opposing practices like sati, female infanticide, and promoting women’s participation in religious activities. |

| Prominent Non-Sectarian Saints | Notable non-sectarian Bhakti saints, such as Kabir and Guru Nanak, played a significant role in bridging the gap between Hindu and Islamic traditions, fostering understanding and harmony. |

| Legacy | Bhakti saints’ ideas continue to influence modern society, emphasizing love, inclusivity, and devotion, forming an essential part of India’s cultural and religious heritage. |

Please note that this table captures the main features of the Bhakti movement based on the given information.

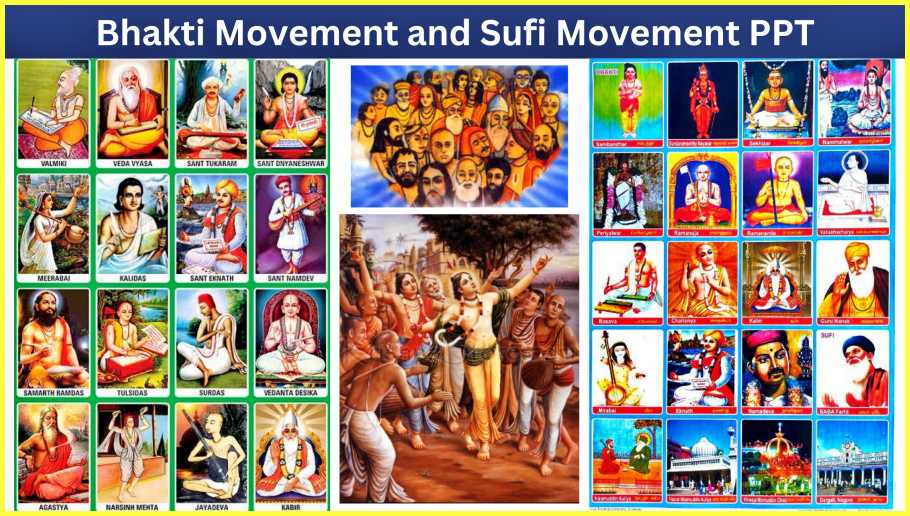

Alvars and Nayanars: Pioneering Saints of the Tamil Bhakti Movement

Alvars: Devotion to Vishnu and Divine Poetry

- The Bhakti movement in Tamil Nadu found its vibrant expression through the Alvars, the devoted followers of Vishnu. Comprising 12 Vaishnavite saints, the Alvars passionately composed poems extolling the virtues of Vishnu. Amidst these revered saints, Andal stood out as the sole female poet-saint, her verses echoing the pure love for Vishnu. These Alvars, hailing from diverse backgrounds and eras, shared a unifying theme: their unwavering devotion and surrender to their personal god. Traveling from village to village, they sang of their profound love for Vishnu, weaving the great Vishnu temples into the tapestry of their compositions. The sanctity of these temples, mentioned in their verses, eventually coalesced into the revered 108 Divya Desams, scattered across Tamil Nadu and Kerala. Their timeless poetry was compiled in the 9th and 10th centuries CE by the Vaishnava theologian Nathamuni, shaping the Naalayira Divya Prabhandham—a revered text containing four thousand verses glorifying Vishnu.

Nayanars: Shiva Devotees and the Tirumurai

- In parallel, the Bhakti movement also found ardent devotees in the form of Nayanars, followers of Shiva. These 63 saints, spanning the 5th to 10th centuries, shared an unbreakable bond rooted in their profound love for Shiva. Noteworthy among them was Appar, whose influence extended to the conversion of Pallava King Mahendravarman to Shaivism between 600 to 630 CE. As Hinduism gained ascendancy, Buddhism and Jainism waned. The poetic legacy of the Nayanars was encapsulated in the Tirumurai, a monumental 12-volume compendium. Compiled over various periods, this collection encompasses 18,426 songs, each a heartfelt dedication to Shiva. Through their verses, these saints not only glorified Shiva but also played a vital role in the cultural and religious tapestry of medieval Tamil Nadu.

Spread and Continuity: Bhakti’s Northward Journey

- The fervor of the Bhakti movement in Tamil Nadu did not confine itself to the region’s boundaries. It embarked on a transformative journey, radiating its spiritual energy to neighboring lands. In the 12th century, the movement found resonance in Karnataka through the works of Basavanna (1105-68 CE). Later, in the 13th century CE, the Varkari movement carried the torch of Bhakti to Maharashtra. This remarkable diffusion of the Bhakti spirit underscored its enduring impact, fostering unity, devotion, and love for the divine across different regions and cultures. The Alvars and Nayanars, through their profound devotion and poetic articulation, became emblematic figures, embodying the essence of the Bhakti movement and leaving an indelible mark on India’s spiritual heritage.

Table: Alvars and Nayanars of Tamil Nadu

Here is the information presented in the form of a table:

| Saints of Tamil Nadu Bhakti Movement | Number of Saints | Deity Worshipped | Significant Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alvars | 12 | Vishnu | Composed poems praising Vishnu. Andal, the lone female poet-saint. Traveled, sang of pure love for Vishnu. Vishnu temples in compositions led to the creation of 108 Divya Desams. Canonized between 9th and 10th centuries CE. |

| Nayanars | 63 | Shiva | Devotion to Shiva. Appar, a prominent saint, converted Pallava King Mahendravarman to Shaivism. Compilation of their poetry in Tirumurai, a 12-volume compendium with 18,426 songs, showcasing their love for Shiva. |

| Spread of the Movement | Movement spread to Karnataka in the 12th century through Basavanna’s works (1105-68 CE) and to Maharashtra in the 13th century CE through the Varkari movement. |

This table summarizes the key aspects of the Alvars and Nayanars of the Tamil Nadu Bhakti movement, including the number of saints, the deities they worshipped, and significant features of their contributions to the movement.

Basavanna: Pioneer of Lingayatism and Social Reformer

In the rich tapestry of India’s Bhakti movement (1105-68), the 12th-century figure Basavanna emerges as a prominent catalyst, especially in the Kannada region. His legacy not only challenged the prevailing caste hierarchy but also left an indelible mark on the social fabric of local society. Basavanna is credited with founding the Lingayat tradition, where the term “Lingayat” denotes an individual who wears a personal linga, an iconic representation of the god Shiva, on their body—a sacred emblem acquired during the initiation ceremony.

Lingayatism: A Unique Spiritual Tradition

- Basavanna’s initiation of the Lingayat tradition was a significant departure from the conventional norms of worship. This movement emphasized a personal, direct connection with the divine, symbolized by the wearing of the linga. Despite the resistance from the orthodox sections of society, Basavanna’s movement gained traction, creating a distinct religious identity within the region.

Vachana Sahitya: A Literary Legacy

- Under Basavanna’s guidance, the Bhakti movement in the Kannada region produced a profound literary tradition known as Vachana Sahitya. These “vachanas,” or pithy aphorisms, were not only spiritual but also socially incisive. Basava himself, alongside his disciples such as Akka Mahadevi, Allama Prabhu, and Devara Dasimayya, contributed to this rich literary heritage. These vachanas communicated astute observations on spiritual and social matters, embodying the essence of the Bhakti movement’s emphasis on direct, heartfelt expression.

Social Reforms and Enduring Influence

- Beyond the realm of literature, Basavanna actively utilized his influence as a minister under King Bijjala to initiate social reform programs. His verses were not mere poetry; they were messages meant for the masses, advocating for social equality and spiritual freedom. Despite facing opposition from orthodox quarters, Basavanna’s ideas endured, shaping a new way of thinking in society. His influence reached far beyond his time, surviving into the modern era. In present-day Karnataka, Basavanna remains an inspirational figure, a symbol of progressive thought and social transformation, continuing to influence the region’s cultural and spiritual landscape.

Table of Basavanna

Here is the information presented in the form of a table:

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Founder | Basavanna (1105-1168 CE) |

| Movement | Initiated Bhakti movement in the Kannada region during the 12th century, challenging the caste hierarchy and societal norms. |

| Tradition Founded | Established Lingayatism, where “Lingayat” refers to an individual wearing a personal linga, an iconic form of god Shiva, received during an initiation ceremony. |

| Literary Contribution | Authored Vachana Sahitya, a collection of pithy aphorisms, along with disciples like Akka Mahadevi, Allama Prabhu, and Devara Dasimayya, conveying profound spiritual and social insights. |

| Social Reforms | Utilized his influence as a minister under King Bijjala to initiate social reform programs, advocating for social equality and spiritual freedom. |

| Legacy | Despite facing opposition from orthodoxy, his ideas shaped modern thinking, making him an enduring inspirational figure in Karnataka, symbolizing progressive thought and social transformation. |

This table encapsulates the key aspects of Basavanna’s contributions to the Bhakti movement and Lingayatism, including his role as a social reformer and his lasting legacy in Karnataka.

Bhakti Blossoms in Maharashtra: The Varkari Tradition

In the vibrant tapestry of Maharashtra’s religious and cultural heritage, the late 13th century witnessed the emergence of the Bhakti movement, which found its devout proponents in the Varkaris. Among the most influential figures of this movement were Jnanadev (1275-96), Namdev (1270-50), and Tukaram (1608-50), whose verses continue to resonate with the spirit of Bhakti, embodying profound devotion and love for the divine.

The Rebel Spirit of Tukaram

- Tukaram, in particular, stood out as a rebel against societal norms and religious orthodoxy. Born into the Shudra caste, traditionally considered lower in the hierarchical social structure, Tukaram defied the limitations imposed by his background. Initially, he pursued a merchant’s life, yet his true calling lay in spirituality. Despite Brahminical injunctions against someone of his status delving into religious matters, Tukaram fearlessly embraced his calling. What set him apart was not just his defiance but also his choice of language. In a time when Sanskrit was often considered the language of religion and literature, Tukaram chose to express his devotion in Marathi, the vernacular language of the people. This decision was revolutionary, breaking down linguistic barriers and making profound religious teachings accessible to the masses.

Marathi Verses: The Essence of Bhakti

- Tukaram, along with his Bhakti contemporaries, left behind a legacy of verses that encapsulate the very essence of the Bhakti movement. Through their poetry, they celebrated a personal connection with the divine, emphasizing love, devotion, and the universality of spiritual experience. Tukaram’s Marathi compositions, in particular, resonated deeply with common folk, forging a profound emotional bond with the divine. His verses became a beacon of inspiration, guiding countless individuals on their spiritual journeys.

Enduring Influence and Cultural Significance

- The rebellious spirit and poetic brilliance of Tukaram, along with his fellow Varkari saints, continue to shape Maharashtra’s cultural and religious landscape. His courage to challenge social norms and express profound spiritual truths in the language of the people made him not only a religious icon but also a symbol of linguistic and social empowerment. Tukaram’s legacy endures, not only in the verses he penned but also in the hearts of those who find solace and inspiration in his words, perpetuating the spirit of Bhakti in Maharashtra and beyond.

Table of Maharashtra

Here is the information presented in the form of a table:

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Bhakti Movement in Maharashtra | The Bhakti movement in Maharashtra commenced in the late 13th century and was led by the Varkaris, devout followers known for their deep spiritual devotion. |

| Prominent Figures | Notable figures of this movement include Jnanadev (1275-1296), Namdev (1270-1350), and Tukaram (1608-1649), whose poetic verses capture the essence of Bhakti and spirituality. |

| Tukaram: The Defiant Saint | Tukaram, a Shudra by caste, defied societal norms by choosing a spiritual path. He transitioned from being a merchant to a revered saint, challenging Brahminical restrictions. |

| Language of Expression | Tukaram boldly expressed his spiritual insights in Marathi, the vernacular language of the people, breaking linguistic barriers and making profound teachings accessible. |

| Legacy and Verses | The enduring legacy of these saints lies in the verses they left behind, encapsulating the core tenets of Bhakti. Tukaram’s rebellious spirit continues to inspire generations. |

This table summarizes the key aspects of the Bhakti movement in Maharashtra, highlighting the notable figures, Tukaram’s defiance against societal norms, the language of expression, and the lasting legacy of the movement’s verses.

Kabir: The Universal Bhakti Poet

In the vast landscape of North India, the profound teachings of Kabir, a revered saint and poet, resonated as a beacon of spiritual wisdom and social reform. Kabir’s philosophy, deeply rooted in personally experienced devotion, transcended religious boundaries. He envisioned a path to God that was based on the essence of bhakti or devotion, emphasizing a personal and direct connection with the divine. For Kabir, the Creator was singular, and this omnipresent deity was known by various names across different religious traditions – Rama, Hari, Govinda, Allah, Rahim, Khuda, and more. This inclusive perspective allowed people from diverse faiths to find resonance in his teachings. Kabir’s universal message bridged religious divides, prompting Muslims to regard him as a Sufi, Hindus to revere him as a Rama-Bhakta, and Sikhs to incorporate his profound verses into the Adi Granth, the holy scripture of Sikhism.

Beyond External Rituals: Kabir’s Spiritual Essence

- Kabir’s spiritual philosophy transcended the external rituals and dogmas of organized religion. He believed that the core of devotion lay in personal experience and genuine love for the divine. The outer trappings of religious practices held little meaning for him, as he delved deep into the essence of devotion through his dohas, short poetic verses that embodied profound spiritual insights. Kabir’s poetry was not confined to the realm of religion; it was a forceful instrument for societal transformation.

A Catalyst for Social Change: Kabir’s Impact on Society

- Kabir was not merely a poet; he was a social reformer whose ideas sought to challenge the narrow and rigid beliefs prevalent in society. His verses carried a powerful and direct message, addressing societal prejudices and advocating for a broader, inclusive mindset. His language was not ornate; it was straightforward and easily comprehensible, allowing his wisdom to permeate everyday conversations. Through his poetry, Kabir inspired individuals to question societal norms, fostering a spirit of critical thinking and compassion.

Legacy in Everyday Language: Kabir’s Lasting Impact

- Kabir’s legacy extends far beyond the confines of history; his verses have become an integral part of everyday language and discourse. His profound ideas, encapsulated in his simple yet eloquent poetry, continue to echo in the hearts and minds of people, reminding them of the power of devotion, unity, and love. Kabir’s teachings have transcended the barriers of time, becoming a timeless source of inspiration for generations, fostering a sense of spiritual connectedness and social harmony in the diverse tapestry of North India’s cultural heritage.

Table of Kabir

Here is the information presented in the form of a table:

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Philosophy | Kabir emphasized the path to God through personally experienced bhakti or devotion, believing in the existence of a singular Creator, known by various names like Rama, Hari, Govinda, Allah, Rahim, Khuda, etc. |

| Recognition by Faiths | Muslims regard Kabir as a Sufi saint, Hindus revere him as Rama-Bhakta, and Sikhs include his songs in the Adi Granth, showcasing his universal appeal across religious boundaries. |

| Literary Contributions | Kabir expressed his beliefs through dohas (Sakhi), short poetic verses characterized by forceful and direct language. His simple yet profound poetry has become a part of everyday language. |

| Social Reform | Kabir challenged narrow societal norms through his poetry, aiming to broaden thinking and promote inclusivity and compassion in society. |

This table summarizes the key aspects of Kabir’s philosophy, recognition across different faiths, literary contributions, and his role as a social reformer.

Nanak: The Visionary Guru

In the annals of religious history, Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, stands as a beacon of spiritual enlightenment and social reform. Born in Talwandi (Nankana Sahib), Guru Nanak exhibited early inclinations towards a spiritual life, displaying remarkable compassion and kindness towards the poor and needy. His disciples, recognizing his profound teachings, identified themselves as Sikhs, a term derived from Sanskrit sisya (disciple) or Pali sikkha (instruction).

Eradicating Corruption and Fostering Equality

- Guru Nanak embarked on a transformative mission to eradicate prevalent corruption and degrading practices deeply embedded in society. His objective was not only religious but profoundly social; he envisioned a new path leading to the establishment of an egalitarian social order. Much like Kabir, Guru Nanak was not just a religious teacher; he was a tireless social reformer. One of his significant contributions was advocating for the improvement in the status of women, challenging the prevailing societal norms. Guru Nanak’s revolutionary stance included affirming the dignity of women, stating that those who give birth to kings should be revered and not subjected to disparagement.

The Guru Granth Sahib: A Sacred Compilation

- The profound wisdom encapsulated in Guru Nanak’s words, along with the teachings of other Sikh Gurus, has been meticulously compiled in the Guru Granth Sahib. This holy scripture of the Sikhs stands as a testament to the spiritual and moral guidance offered by Guru Nanak and subsequent Gurus. The Guru Granth Sahib, revered as the eternal Guru in Sikhism, serves as a timeless source of inspiration, encompassing not only religious doctrines but also the principles of social justice, equality, and compassion.

Guru Nanak’s legacy endures not only within the Sikh community but also resonates globally, emphasizing the importance of spirituality, social reform, and gender equality. His teachings continue to inspire countless individuals, transcending the boundaries of time and culture, and fostering a sense of unity and compassion in the diverse tapestry of humanity.

Table of GURU Nanak

Here is the information presented in the form of a table:

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Birthplace | Talwandi (Nankana Sahib) |

| Early Inclination | Showed spiritual leanings from an early age; exhibited kindness and assistance to the poor and needy. |

| Disciples | His followers identified themselves as Sikhs, a term derived from Sanskrit sisya (disciple) or Pali sikkha (instruction). |

| Objectives | Aimed to eradicate corruption and degrading practices in society; advocated for the establishment of an egalitarian social order. |

| Social Reformer | Much like Kabir, Guru Nanak was both a religious teacher and a social reformer; emphasized improving the status of women, advocating respect for mothers who give birth to kings. |

| Compilation of Teachings | His teachings, along with those of other Sikh Gurus, were compiled in the Guru Granth Sahib, the holy scripture of Sikhs, serving as a timeless guide for spirituality and social ethics. |

This table summarizes the key aspects of Guru Nanak’s life, including his birthplace, early inclinations, influence on his disciples, objectives as a social reformer, and the compilation of his teachings in the Guru Granth Sahib.

Ravi Das: A Voice of Equality and Social Justice

In the historical tapestry of 15th and 16th century India, a remarkable figure emerged, near-contemporary to Guru Nanak, who echoed the call for a casteless society. Ravi Das (1450-1520), born into a family of leather workers in the sacred city of Varanasi, stood as a testament to the enduring spirit of social reform and equality. Much like Guru Nanak, Ravi Das passionately advocated for a society free from the shackles of caste discrimination, transcending the societal norms of his time.

A Life of Struggles and Perseverance

- What set Ravi Das apart was his personal experience of the harsh realities of caste discrimination. As a member of an untouchable caste, he bore the brunt of societal prejudices and exclusion. Despite facing these adversities, Ravi Das fearlessly confronted the existing social hierarchy, emphasizing the intrinsic worth and equality of every individual regardless of their birth.

A Casteless Society: Ravi Das’s Vision

- Ravi Das, through his teachings and actions, championed the cause of a casteless society. His message resonated deeply with the marginalized communities, offering hope and empowerment. His vision went beyond mere rhetoric; he lived the challenges faced by the untouchables, infusing his teachings with authenticity and empathy. In a society rigidly bound by caste divisions, Ravi Das’s message was a beacon of hope, calling for an end to discrimination and the establishment of social justice and equality.

Legacy and Inspiration

- Ravi Das’s legacy endures, not only in the pages of history but also in the hearts of those who continue to fight against social injustices. His life and teachings inspire generations, serving as a reminder of the importance of standing up against discrimination and advocating for a society where every individual is valued for their inherent worth, transcending the constraints of caste, class, or creed. In the face of adversity, Ravi Das’s courage and conviction serve as a timeless testament to the transformative power of social reform and the enduring quest for a more just and equitable world.

Table of Ravi Das

Here is the information presented in the form of a table:

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Birth and Background | Ravi Das was born in 1450 into a family of leather workers in Varanasi. |

| Contemporary of Nanak | Ravi Das lived during the same period as Guru Nanak, making him a near-contemporary of the Sikh spiritual leader. |

| Advocate for Equality | Similar to Guru Nanak, Ravi Das emphasized the need for a casteless society, challenging the prevalent caste system. |

| Untouchable Caste | Ravi Das belonged to the untouchable caste and personally experienced the discrimination he spoke out against. |

| Social Reform | He advocated for a society free from caste discrimination, offering a vision of equality and social justice. |

| Legacy | Ravi Das’s teachings continue to inspire generations, highlighting the importance of social equality and justice. |

This table summarizes the key aspects of Ravi Das’s life, including his birth and background, his contemporaneity with Guru Nanak, his advocacy for a casteless society, his personal experience with untouchability, his social reform efforts, and his enduring legacy as an advocate for social equality.

In the rich tapestry of medieval India, alongside the Bhakti movement that championed a direct and personal connection with the divine, another powerful wave surged forth – the Vaishnavite movement. This movement, rooted in unwavering devotion toward a sakar (manifest) form of God, found its focal points in the worship of revered deities like Rama and Krishna. Prominent figures like Surdas, Mirabai, Tulsidas, and Chaitanya became the torchbearers of this movement, articulating their spiritual beliefs through the medium of poetry, song, dance, and the vibrant tradition of kirtans.

Surdas and the Melodious Devotion to Krishna

- Surdas, a disciple of the renowned teacher Vallabhachara, emerged as a notable figure in the Vaishnavite movement. Despite being blind, Surdas’s poetic prowess knew no bounds. His compositions, centered around the enchanting exploits of Krishna during his childhood and youth, exuded a gentle affection and delightful charm. His magnum opus, Sursagar, vividly recounted the endearing tales of Krishna, captivating the hearts of listeners and readers alike.

Chaitanya: Embracing the Divine Essence of Krishna

- In the eastern realms of India, the Vaishnavite movement found a fervent advocate in Chaitanya. For Chaitanya, Krishna was not merely an incarnation of Vishnu; he was the ultimate embodiment of the divine. Chaitanya’s devotion for Krishna found expression through Sankirtans – hymn sessions conducted by ardent devotees. These vibrant sessions resonated in homes, temples, and even street processions, fostering a palpable sense of spiritual fervor among the masses.

Rama Bhakti and the Inclusive Teachings of Saints

- While Krishna worship flourished, the adoration for Lord Rama was also propagated by revered saints like Ramananda. Ramananda, a significant proponent of the Vaishnavite movement, regarded Rama as the supreme God. What set these saints apart was their remarkable inclusivity; they welcomed women and outcastes into the folds of their devotional practices, breaking societal barriers and fostering a spirit of equality and acceptance.

Tulsidas and the Ramacharitmanas: Epitome of Devotion

- Among the luminaries of Rama bhaktas, Tulsidas shone brightly. His magnum opus, the Ramacharitmanas, stands as a testament to his profound devotion and literary brilliance. Through this epic work, Tulsidas not only captured the essence of Rama’s life and teachings but also elevated the spirit of devotion to new heights, leaving an indelible mark on the spiritual landscape of India.

Philosophical Underpinnings: Reforms and Humanism

- The Vaishnavite saints, within the broad framework of Hinduism, propagated a philosophy rooted in love, devotion, and humanism. Their teachings emphasized religious reforms and the cultivation of love and harmony among fellow beings. In embracing the sakar forms of God, these saints not only deepened their own spiritual experiences but also enriched the lives of countless devotees, fostering a sense of unity and reverence that continues to echo through the annals of Indian spirituality.

Here is the information presented in the form of a table:

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Main Exponents | Surdas, Mirabai, Tulsidas, Chaitanya |

| Worshipped Deities | Rama and Krishna |

| Expression of Devotion | Through poetry, song, dance, and kirtans |

| Surdas (1483-1563) | Disciple of Vallabhachara; Blind poet; Songs centered around Krishna; Notable work – Sursagar, depicting Krishna’s childhood and youth with affection. |

| Chaitanya (1484-1533) | Considered Krishna as the highest form of God; Devotion expressed through Sankirtans in homes, temples, and street processions. |

| Ramananda (1400-1470) | Popularized worship of Rama as the supreme God; Welcomed women and outcastes into devotional practices. |

| Tulsidas (1532-1623) | Famous Rama bhakta; Wrote Ramacharitmanas, an epic poem depicting the life of Rama. |

| Philosophical Approach | Developed within the broad framework of Hinduism; Emphasized religious reforms, love among beings, and humanism. |

| Spread of the Movement | Spread in the east through the efforts of Chaitanya; Notable saints like Ramananda and Tulsidas played significant roles in popularizing Rama and Krishna worship. |

| Key Themes | Worship of Rama and Krishna; Inclusivity, welcoming women and outcastes; Emphasis on poetry, song, dance, and kirtans as mediums of devotion. |

| Impact and Legacy | Enduring influence on Hindu devotional practices; Contributions to Indian literature and cultural traditions; Continued reverence for Rama and Krishna. |

This table summarizes the key aspects of the Vaishnavite Movement, including its main exponents, worshipped deities, expressions of devotion, notable figures like Surdas, Chaitanya, Ramananda, and Tulsidas, philosophical approach, spread of the movement, key themes, and its lasting impact and legacy.

What is Sufi movement?

The Sufi movement is a mystical and spiritual movement within Islam that emphasizes the inward search for God and a direct, personal experience of the divine. Sufism, derived from the Arabic word “suf,” meaning wool, originally referred to the coarse woolen robes worn by early Sufi practitioners as a symbol of their rejection of worldly luxuries. Over time, Sufism evolved into a rich tradition of spirituality, focusing on love, devotion, and the purification of the soul.

Key Aspects of the Sufi Movement:

- Mystical Experience: Sufis seek to achieve a deep, intimate connection with God through spiritual practices, meditation, chanting, and other rituals. They believe in experiencing the divine directly and personally, transcending the formalities of religious doctrine.

- Love and Devotion: Love for God (Ishq) and spiritual devotion (Tawhid) are central themes in Sufism. Sufi practitioners often express their love for God through poetry, music, and dance, emphasizing the emotional and transformative aspects of their faith.

- Guidance through Sufi Orders: Sufism is organized into various Sufi orders or brotherhoods, each led by a spiritual master known as a Sufi saint or pir. These orders serve as spiritual communities where disciples gather for guidance, learning, and communal worship.

- Concept of Tariqa: Tariqa refers to the spiritual path or way in Sufism. It involves a set of practices, teachings, and rituals prescribed by the Sufi master to guide disciples on their spiritual journey.

Example of Sufi Practices:

- One of the most famous Sufi practices is Sama or Sufi Whirling, associated with the Mevlevi Order founded by the poet and mystic Rumi. During Sama, practitioners, also known as dervishes, engage in a meditative dance accompanied by music played on traditional Sufi instruments. The whirling motion is symbolic of the soul’s journey towards spiritual enlightenment and union with the divine. Through the repetitive spinning, Sufis aim to detach from worldly concerns and reach a state of spiritual ecstasy.

Impact and Legacy:

- The Sufi movement has significantly influenced Islamic culture and spirituality throughout history. Sufi poetry, music, and teachings have contributed to the cultural heritage of various countries, transcending religious boundaries and fostering a universal understanding of divine love.

Sufism’s emphasis on love, tolerance, and inner peace has played a crucial role in shaping the spiritual landscape of Islam, emphasizing the importance of the individual’s relationship with God. Sufi teachings continue to inspire people around the world, promoting a message of harmony, compassion, and unity.

The Emergence of Sufi Mysticism

The Sufi movement, a mystical and spiritual dimension within Islam, emerged amidst the backdrop of orthodox Sunni Islam in the medieval period. Within the Sunni community, various schools of Islamic Law existed, each with its own distinct interpretations and practices. Among these, the Hanafi school, adopted by the eastern Turks, eventually made its way to India, becoming prominent within the region.

The Conflict of Ideas: Mutazilas, Ashari School, and Al-Ghazali

- During this period, orthodox Sunnism faced challenges from the rationalist Mutazilas, who advocated strict monotheism and believed in human free will and personal responsibility for one’s actions. Opposing them, the Ashari School, founded by Abul Hasan Ashari, defended the orthodox doctrine through rationalist arguments. One of the most influential scholars of this school was Abu Hamid al-Ghazali, credited with reconciling orthodoxy with mysticism. His ideas found widespread acceptance, especially due to the new educational system established by the state.

Ulema and Sufis: Divergent Paths

- In the face of political and religious degeneration, two distinct groups emerged within the Muslim community. The ulema, scholars who followed orthodox Sunni beliefs, played a significant role in medieval Indian politics. In contrast, the Sufis, a group of mystics, opposed the materialism and formalism within the religious and political spheres. They emphasized free thought, liberal ideas, and a deep personal connection with the divine.

Sufi Practices and Philosophy

- Sufism, rooted in meditation and spiritual reflection, advocated love for God and service to humanity. Sufi mystics interpreted religion as a profound love for the divine, transcending mere rituals. They organized themselves into different silsilahs or orders, each led by a spiritual guide called a pir or Khwaja. These Sufi leaders, along with their disciples, resided in hospices known as khanqahs. The Sufis organized rituals called samas, involving the recital of holy songs, aimed at inducing mystical ecstasy among the participants.

Sufism: A Liberal Movement within Islam

- It is crucial to understand that the Sufi saints were not establishing a new religion; instead, they were fostering a more liberal movement within the framework of Islam. While adhering to the Quran, the Sufis promoted a spiritual path marked by love, devotion, and service, thereby paving the way for a more compassionate and inclusive approach within the Islamic tradition. Their enduring influence has left a profound impact on Islamic spirituality and religious practices, emphasizing the significance of love and unity in the pursuit of the divine.

Table: Sufi Movement and Its Philosophical Context

| Aspects | Description |

|---|---|

| Schools of Islamic Law | Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi’i, Hanbali – Among these, the Hanafi school, originating in the eighth century, was adopted by the eastern Turks and later in India. |

| Challenges to Orthodoxy | The Mutazilas advocated strict monotheism, emphasizing human free will and individual responsibility for actions. They were countered by the Ashari School, led by Abu Hamid al-Ghazali, who reconciled orthodoxy with mysticism. |

| Role of Ulema and State | Ulema, scholars familiar with Ashari ideas, played a pivotal role in the politics of medieval India. They were instrumental in shaping government policies in accordance with orthodox Sunni beliefs. |

| Contrast with Ulema | Sufis, mystics appalled by societal degeneration, opposed the ostentatious display of wealth and the ulema’s readiness to serve ungodly rulers. They emphasized free thought, meditation, and spiritual exploration. |

| Sufi Philosophical Tenets | Sufis stressed free thought, liberal ideas, and opposed formal worship, religious rigidity, and fanaticism. They sought religious fulfillment through meditation and interpreted religion as love for God and service to humanity. |

| Sufi Organizational Structure | Sufis organized into different silsilahs (orders) with their own spiritual guides called Khwaja or Sheikh. They resided in hospices (khanqahs) and conducted rituals, such as samas (recitals of holy songs), to induce mystical ecstasy. |

| Sufi Influence and Allegiance | Sufi saints were not establishing a new religion but fostering a more liberal movement within Islam. They upheld allegiance to the Quran while championing a compassionate, inclusive, and spiritual approach to Islamic teachings. |

This table summarizes the key aspects of the Sufi movement, its challenges to orthodoxy, its contrast with the ulema, philosophical beliefs, organizational structure, and its influence within the framework of Islam.

Sufism’s Early Presence in India

The advent of Sufism in India is traced back to the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Notable among the early Sufi scholars who settled in India was Al-Hujwari, popularly known as Data Ganj Baksh (Distributor of Unlimited Treasure), who died in 1089. Initially, the primary centers of Sufism were established in Multan and Punjab regions.

Expansion to Different Regions:

- As centuries passed, the influence of Sufism spread far and wide. By the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Sufi orders had extended their presence to various regions in India, including Kashmir, Bihar, Bengal, and the Deccan. The diverse cultural landscape of India provided fertile ground for the growth of different Sufi orders.

Sufi Silsilahs and Their Classification:

- In his work Ain-i-Akbari, Abul Fazl categorized the Sufi orders into fourteen silsilahs. These orders were further divided into two types: Ba-shara and Be-shara. The Ba-shara orders adhered to the principles of Islamic Law (Sharia), encompassing religious practices like namaz (prayer) and roza (fasting). Notable among these orders were Chishti, Suhrawardi, Firdawsi, Qadiri, and Naqshbandi silsilahs.

The Unique Beshara Silsilahs:

- In contrast, the beshara silsilahs were distinctive for not strictly adhering to the Sharia. One such group within this category was the Qalandars. These Sufi orders not bound by conventional Islamic law often pursued a more unconventional and mystic path in their spiritual practices. The Qalandars, among others, exemplified the diversity within the Sufi traditions in India, reflecting the multifaceted nature of Sufism in the country.

Table: Sufism in India

| Aspect | Information |

|---|---|

| Advent of Sufism in India | 11th and 12th centuries |

| Prominent Early Sufi Scholar | Al-Hujwari (Died in 1089), popularly known as Data Ganj Baksh |

| Initial Centers of Sufism | Multan and Punjab |

| Spread of Sufism | Kashmir, Bihar, Bengal, and the Deccan |

| Sufi Scholar Mentioned | Abul Fazl in the Ain-i-Akbari |

| Number of Sufi Silsilahs | Fourteen |

| Types of Silsilahs | – Ba-shara (Following Sharia) |

| – Be-shara (Not bound by Sharia) | |

| Prominent Ba-shara Orders | – Chishti |

| – Suhrawardi | |

| – Firdawsi | |

| – Qadiri | |

| – Naqshbandi | |

| Prominent Be-shara Orders | – Qalandars |

Chishti Silsilah: Spreading the Light of Devotion

The Chishti Silsilah, a prominent Sufi order, traces its origins to a village named Khwaja Chishti near Herat. In India, this influential spiritual tradition was established by Khwaja Muinuddin Chishti, who arrived around 1192 and made Ajmer the epicenter of his teachings. His philosophy was rooted in the belief that the highest form of devotion was in serving humanity, particularly the downtrodden. Khwaja Muinuddin’s impact was profound, shaping the ethos of the region. Upon his passing in 1236, Ajmer gained significance as a pilgrimage site, frequented by emperors during the Mughal era.

- Among his notable disciples were Sheikh Hamiduddin of Nagaur and Qutubuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki. Sheikh Hamiduddin, adopting a humble lifestyle, declined offers of wealth, emphasizing the essence of simplicity and detachment. Qutubuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki’s khanqah (spiritual retreat) welcomed people from diverse backgrounds, making it a hub of spiritual learning. Sultan Iltutmish even dedicated the iconic Qutub Minar to Bakhtiyar Kaki, underscoring his significance in medieval Delhi.

The Legacy of Baba Farid and Sheikh Nizamuddin Auliya:

- Baba Fariduddin, known as Baba Farid, was instrumental in spreading the Chishti tradition in modern Haryana and Punjab. He transcended religious boundaries, earning respect from both Hindus and Muslims. His Punjabi verses found a place in the Adi Granth, a scripture revered by Sikhs. Baba Farid’s most eminent disciple, Sheikh Nizamuddin Auliya, profoundly impacted Delhi, making it a pivotal center of the Chishti Silsilah. Arriving in Delhi in 1259, he chose a life of simplicity, distancing himself from political entanglements. For him, renunciation meant the altruistic distribution of food and clothing to the needy. Among his followers was the renowned writer and poet, Amir Khusrau.

The Journey Towards Eastern and Southern India:

- Following the passing of Sheikh Nasiruddin Mahmud, also known as Nasiruddin Chirag-i-Dilli (The Lamp of Delhi), and the absence of a designated spiritual successor, the disciples of the Chishti Silsilah dispersed towards eastern and southern regions of India. Their teachings continued to illuminate the spiritual landscape, emphasizing the values of service, simplicity, and universal love, thus leaving an indelible mark on the tapestry of Indian Sufism.

Table of Chishti Silsilah

| Chishti Silsilah Saints | Significant Contributions |

|---|---|

| Khwaja Muinuddin Chishti | Founded the Chishti Silsilah in India, emphasizing service to humanity. Made Ajmer a major center of spiritual learning. |

| Sheikh Hamiduddin | Lived a humble life, refusing grants and cultivating land. |

| Qutubuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki | Established a renowned khanqah, visited by people from diverse backgrounds. Sultan Iltutmish dedicated Qutub Minar to him. |

| Sheikh Fariduddin (Baba Farid) | Popularized Chishti Silsilah in Haryana and Punjab. Revered by Hindus and Muslims. His Punjabi verses are quoted in Adi Granth. |

| Shaikh Nizamuddin Auliya | Made Delhi a prominent center of the Chishti Silsilah. Emphasized renunciation through service to the poor. Influenced Amir Khusrau. |

| Sheikh Nasiruddin Mahmud | Also known as Nasiruddin Chirag-i-Dilli. His disciples spread the Chishti tradition in eastern and southern India. |

Suhrawardi Silsilah: Embracing State Connections

The Suhrawardi Silsilah, a Sufi order founded by Sheikh Shihabuddin Suhrawardi, found its roots in India under the influence of Sheikh Bahauddin Zakariya. Sheikh Bahauddin Zakariya, born in 1182, played a pivotal role in establishing this silsilah in the Indian subcontinent. He set up a prominent khanqah (Sufi lodge) in Multan, a city located in present-day Pakistan. This khanqah quickly gained prominence, drawing the attention of rulers, high-ranking government officials, and affluent merchants.

- Unlike some other Sufi orders, the Suhrawardi saints had a distinctive approach in their interactions with the ruling powers of the time. Sheikh Bahauddin Zakariya openly sided with Sultan Iltutmish during his struggle against Qabacha, a rival ruler. In recognition of his loyalty and contributions, Sultan Iltutmish conferred upon him the esteemed title of Shaikhul Islam (Leader of Islam). This alliance with the state authorities set the Suhrawardi silsilah apart from other Sufi orders in India.

In contrast to certain Sufi traditions, particularly the Chishti saints who often maintained a degree of separation from political affairs, the Suhrawardi saints actively engaged with the state apparatus. They readily accepted gifts, jagirs (land grants), and even held positions within the ecclesiastical department of the government. This close association with the ruling powers enabled the Suhrawardi Silsilah to establish a stable presence in regions like Punjab and Sind. Their willingness to align with political authorities underscored a pragmatic approach, demonstrating the diverse strategies employed by Sufi orders in medieval India to propagate their teachings and establish their influence.

Table of Suhrawardi Silsilah

| Suhrawardi Silsilah | |

|---|---|

| Founder | Sheikh Shihabuddin Suhrawardi |

| Established in India | Sheikh Bahauddin Zakariya (1182-1262) |

| Prominent Location | Multan, Punjab, and Sind |

| Patronage | Rulers, high government officials, and rich merchants |

| Political Affiliation | Active engagement with the state, including accepting gifts, jagirs, and government posts in the ecclesiastical department |

| Notable Act | Sheikh Bahauddin Zakariya openly supported Sultan Iltutmish in his struggle against Qabacha, receiving the title Shaikhul Islam (Leader of Islam) from him |

Firdawsi Silsilah in India

The Firdawsi Silsilah, a branch of the Suhrawardi Silsilah, found its way to India through the efforts of Syed Badruddin Samarqandi, who introduced this spiritual lineage to the Indian subcontinent. Syed Badruddin Samarqandi was a close friend and contemporary of the renowned Sufi saint Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya, indicating the interconnectedness of various Sufi traditions in the region. Once introduced, the Firdawsi Silsilah gained prominence and influence within the spiritual landscape of India.

Shaikh Sharfuddin Yahya: Popularizer of the Firdawsi Silsilah

- The propagation and popularization of the Firdawsi Silsilah in India were notably spearheaded by Shaikh Sharfuddin Yahya, a prominent figure within the Sufi tradition. Under his guidance and influence, this particular silsilah found a foothold in the hearts of Indian devotees. Shaikh Sharfuddin Yahya’s teachings and spiritual practices likely played a significant role in shaping the unique characteristics and beliefs associated with the Firdawsi Silsilah in the Indian context.

While the specific doctrines and practices of the Firdawsi Silsilah in India are not detailed in the provided information, it is evident that this spiritual lineage, like many others, contributed to the rich tapestry of Sufi traditions within the country. The influence of Sufism, represented by various silsilahs, has had a profound impact on the spiritual and cultural heritage of India, fostering a deep sense of devotion, inclusivity, and interconnectedness among its followers.

Table: Firdawsi Silsilah in India

| Key Figures | Contributions |

|---|---|

| Syed Badruddin Samarqandi | Introduced Firdawsi Silsilah to India, a branch of the Suhrawardi Silsilah. Close associate of Hazrat Nizamuddin Auliya. |

| Shaikh Sharfuddin Yahya | Played a crucial role in propagating and popularizing the Firdawsi Silsilah in India. His teachings influenced the spiritual practices of the silsilah within the Indian context. |

Please note that the specific doctrines and practices of the Firdawsi Silsilah in India were not detailed in the provided information.

Shattari Silsilah in India

The Shattari Silsilah found its roots in India through the efforts of Abdullah Shattari, who was a great-grandson, belonging to the fifth generation, of Sheikh Shihabuddin Suhrawardi. This spiritual lineage, like many others in the Sufi tradition, was introduced in India during the Lodhi Dynasty, marking a period of significant cultural and religious exchange in the country. The arrival of the Shattari Silsilah added to the diverse tapestry of Sufi traditions that flourished in India, each with its unique teachings and practices aimed at spiritual enlightenment and devotion.

Tansen: A Notable Follower

- One of the noteworthy followers of the Shattari Silsilah was the legendary musician and composer Tansen. Tansen, whose full name was Miyan Tansen, was a prominent figure in the court of the Mughal emperor Akbar. He was not only a gifted musician but also a devout adherent of the Shattari order. His association with this Sufi lineage showcased the interconnectedness of art, music, and spirituality in the cultural landscape of medieval India. Tansen’s influence as a musician and his spiritual affiliation with the Shattari Silsilah left an indelible mark on the musical traditions of the region, emphasizing the harmony between artistic expression and religious devotion.

While the specific teachings and practices of the Shattari Silsilah in India are not detailed in the provided information, its presence, especially with notable followers like Tansen, highlights the diverse and enriching influence of Sufi traditions on various aspects of Indian society, including music and the arts. The Shattari Silsilah’s legacy continues to be a part of the intricate mosaic of spiritual heritage that characterizes the country.

Table: Shattari Silsilah

| Sufi Silsilah: | Shattari Silsilah |

|---|---|

| Founder: | Abdullah Shattari |

| Introduction in India: | During the Lodhi Dynasty |

| Prominent Follower: | Tansen |

| Lineage Connection: | Abdullah Shattari, a fifth-generation great-grandson of Sheikh Shihabuddin Suhrawardi, established the Shattari Silsilah in India. This spiritual lineage became prominent during the Lodhi Dynasty period. The legendary musician Tansen was one of the notable followers of this order, illustrating the diverse influences of Sufi traditions in Indian society, including the realm of arts and culture. |

Qadiri Silsilah: Sufi Tradition in India

The Qadiri Silsilah, a prominent Sufi order, found its roots in India during the reign of Babur through the efforts of Niyammad-ulla-Qadiri. This spiritual lineage, which traces its origins to the renowned Sufi saint Abdul-Qadir Gilani, gained influence and recognition in the Indian subcontinent during the Mughal era. Niyammad-ulla-Qadiri’s propagation of the Qadiri order marked an important chapter in the rich tapestry of Sufi traditions in India, contributing to the spiritual and cultural diversity of the region.

Dara Shikoh: A Notable Follower:

- One of the significant followers of the Qadiri Silsilah was Dara Shikoh, the eldest son of Emperor Shah Jahan. Dara Shikoh, a scholarly and spiritually inclined prince, embraced the teachings and practices of the Qadiri order. His association with the Qadiri Silsilah reflected the influence of Sufism on the Mughal elite, showcasing how these mystical traditions transcended social and political boundaries, leaving a lasting impact on the cultural milieu of the time.

Challenges During Aurangazeb’s Reign:

- However, the patronage and support for the Qadiri order faced challenges during the rule of Emperor Aurangzeb. Aurangzeb’s policies, characterized by a strict adherence to orthodox Sunni Islam, led to a decline in patronage for various Sufi orders, including the Qadiri Silsilah. The decline in royal favor impacted the Qadiri Sufis, as the state-sponsored support waned under Aurangzeb’s rule, reshaping the dynamics of Sufi influence in the Mughal court and society at large.

Despite these challenges, the Qadiri Silsilah, like other Sufi traditions, continued to persevere and thrive in different ways, adapting to changing political landscapes while maintaining their spiritual teachings and practices. The Qadiri order’s historical presence in India highlights the enduring legacy of Sufism, emphasizing its resilience in the face of evolving political climates and its enduring impact on the spiritual fabric of the country.

Here’s the information presented in a table format:

| Silsilah Name | Introduction in India | Notable Follower | Challenges Faced |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qadiri Silsilah | Established during Babur’s reign by Niyammad-ulla-Qadiri | Dara Shikoh, the eldest son of Shah Jahan | Loss of patronage during Aurangzeb’s reign |

Naqshbandi Silsilah: Upholding Orthodoxy in India

The Naqshbandi Silsilah, a Sufi order known for its orthodoxy, traces its origins to Khwaja Baqi Billah, a devoted disciple of Khwaja Bahauddin Naqshbandi. In comparison to other Sufi orders, the followers of Naqshbandiyya were notably orthodox in their beliefs and practices. The order gained prominence in India due to the influence of Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire, who held deep devotion for the Naqshbandiyya leader Khwaja Ubaidullah Ahrar. Under Babur’s patronage, the Naqshbandi order found a significant following in the Indian subcontinent, with adherents valuing its strict adherence to traditional Sufi principles.

Babur’s Patronage and the Rise of Naqshbandiyya in India

- Babur, the first Mughal emperor, played a pivotal role in popularizing the Naqshbandi order in India. His profound reverence for Khwaja Ubaidullah Ahrar, a revered Naqshbandiyya leader, led to the rapid spread of the order in the Indian subcontinent. Babur’s patronage provided a significant boost to the Naqshbandiyya Sufis, establishing a firm foundation for the order in the diverse religious landscape of India.

Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi: Upholding Orthodoxy in the Face of Change

- One of the notable figures associated with the Naqshbandi Silsilah in India was Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi. He emerged as a staunch proponent of orthodox Islamic practices during a time when the Mughal Emperor Akbar was promoting syncretic and secular beliefs. Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi vehemently opposed the secular practices and beliefs of Akbar, particularly his policies of religious tolerance. He demanded the re-imposition of Jizyah, a tax historically levied on non-Muslims in Islamic states, and advocated for a return to strict adherence to Islamic principles. His efforts to preserve orthodox beliefs within the Naqshbandiyya order marked a significant chapter in the history of Sufism in India, showcasing the diversity of religious thought and practice in the region.

Bhakti Philosophies in Medieval India

In medieval India, the philosophical landscape was profoundly shaped by the religious movements led by mystics and Bhakti saints. These spiritual leaders played a pivotal role in reshaping the religious ideas and beliefs of the time. Among them, prominent figures like Adi Shankaracharya, Vallabhacharya, Ramanuja, and Nimbaraka emerged as influential thinkers, introducing new philosophical paradigms rooted in the teachings of Shankaracharya’s advaita (non-dualism) philosophy.

Adi Shankaracharya and Advaita Philosophy:

- Adi Shankaracharya, a revered saint and philosopher, laid the foundation for the advaita philosophy, emphasizing the concept of non-dualism. According to advaita, the ultimate reality (Brahman) is without attributes and distinctions, and the individual soul (Atman) is inherently one with Brahman. Shankaracharya’s teachings emphasized the unity of the self with the divine, challenging conventional dualistic beliefs prevalent in medieval India.

Contributions of Bhakti Saints:

- In addition to Shankaracharya, Bhakti saints like Vallabhacharya, Ramanuja, and Nimbaraka introduced distinctive philosophical perspectives within the Bhakti tradition. Vallabhacharya emphasized the concept of “Shuddhadvaita,” asserting that the individual soul is eternally connected to God and achieves liberation through loving devotion. Ramanuja, on the other hand, advocated “Vishishtadvaita,” a qualified non-dualism that highlighted the individual soul’s eternal relationship with God while acknowledging the soul’s distinct identity. Nimbaraka contributed to the Bhakti philosophy through his school of thought, emphasizing devotion to Lord Krishna and the worship of his divine forms.

Impact and Legacy:

- These philosophical developments in medieval India not only influenced religious practices but also had a lasting impact on the socio-cultural fabric of the country. The teachings of these mystics and philosophers fostered a sense of spiritual unity, emphasizing devotion, love, and the interconnectedness of all beings. The Bhakti philosophies served as a guiding light for millions, transcending traditional barriers and fostering a profound sense of spirituality among the masses.

| Philosopher | Philosophy Contribution |

|---|---|

| Adi Shankaracharya | Founded advaita philosophy, emphasizing non-dualism |

| Vallabhacharya | Introduced “Shuddhadvaita,” emphasizing loving devotion and eternal connection with God |

| Ramanuja | Advocated “Vishishtadvaita,” a qualified non-dualism emphasizing individual soul’s relationship with God |

| Nimbaraka | Emphasized devotion to Lord Krishna and the worship of his divine forms within the Bhakti tradition |

Advaita by Sankaracharya: Unraveling the Essence of Oneness

Sankaracharya, a luminary thinker and philosopher, emerged as a guiding force during the Hindu revivalist movement in the 9th century. Hailing from the town of Kaladi in Kerala, he became a torchbearer of the Advaita philosophy, also known as Monism. In the realm of Advaita, the world’s reality is refuted, and Brahman, the ultimate reality, stands as the sole existence. It is in the depth of Brahman that reality finds its essence, rendering all else as mere illusion.

Nirgunabrahman: God Without Attributes:

- At the core of Sankaracharya’s teachings was the concept of Nirgunabrahman, the formless, attributeless representation of the divine. This vision of God without attributes emphasized the transcendental nature of Brahman, beyond the confines of human comprehension. Sankaracharya’s philosophical doctrine challenged conventional beliefs, urging individuals to look beyond the apparent reality of the material world.

Eternal Wisdom in Sankaracharya’s Words:

- Sankaracharya’s wisdom echoed through his profound sayings. One of his most celebrated quotes, “Brahma Satyam Jagat Mithya Jivo Brahmatra Naparaha” encapsulated his philosophy. It translates to, “The Absolute Spirit is the reality, the world of appearance is Maya.” Here, he highlighted the illusory nature of the world, emphasizing the eternal truth of Brahman.

Knowledge as the Path to Salvation:

- According to Sankaracharya, salvation could be attained solely through knowledge or ‘gyaan.’ This emphasis on spiritual enlightenment as the key to liberation distinguished his teachings. In his pursuit of spreading knowledge, he wrote commentaries on foundational texts such as the Bhagvat Gita, Brahmasutra, and the Upanishads. His literary contributions included works like “Upadesh Shastri,” “Vivek Chudamani,” and the devotional hymn “Bhaja Govindum Stotra.”

Establishing Spiritual Centers:

- Sankaracharya’s impact extended beyond philosophy; he established mathas, monastic centers, at key pilgrimage sites: Sringiri, Dwarka, Puri, and Badrinath. These mathas became bastions of spiritual learning, preserving and propagating his teachings. Through his philosophical brilliance and spiritual guidance, Sankaracharya left an indelible mark on Hinduism, shaping the understanding of oneness and the pursuit of ultimate truth.

Table: Advaita Philosophy by Sankaracharya

| Aspects | Details |

|---|---|

| Philosophical System | Advaita (Monism) Philosophy |

| Concept of God | Nirgunabrahman (God Without Attributes) |

| Central Tenet | Denial of Reality in the World; Brahman as the Only Ultimate Reality |

| Famous Quote | “Brahma Satyam Jagat Mithya Jivo Brahmatra Naparaha” – “The Absolute Spirit is the reality, the world of appearance is Maya” |

| Path to Salvation | Gyaan (Knowledge) as the Sole Path to Salvation |

| Key Texts | Commentary on the Bhagvat Gita, Brahmasutra, and Upanishads; Writings like Upadesh Shastri, Vivek Chudamani, Bhaja Govindum Stotra |

| Established Mathas | Sringiri, Dwarka, Puri, Badrinath |

Sankaracharya, a profound thinker and leader, introduced the Advaita philosophy, emphasizing the concept of Nirgunabrahman. This philosophical system denied the reality of the material world, recognizing only Brahman as the ultimate truth. His notable quote underscored the illusory nature of the world. Salvation, in his teachings, was attainable solely through knowledge (gyaan). He authored commentaries on foundational texts and wrote significant works like Upadesh Shastri, Vivek Chudamani, and Bhaja Govindum Stotra. Sankaracharya established mathas in pilgrimage centers like Sringiri, Dwarka, Puri, and Badrinath, leaving an enduring legacy in Hindu philosophy.

Vishistadvaita of Ramanujacharya

Introduction to Vishistadvaita: Vishistadvaita, a philosophical concept propounded by the eminent scholar Ramanujacharya, translates to “modified monism.” Unlike pure monism, Vishistadvaita acknowledges a nuanced relationship between the ultimate reality and the world.

Ultimate Reality in Vishistadvaita: According to this philosophy, the ultimate reality is Brahman, denoting God. In Vishistadvaita, Brahman is not isolated from the world; instead, matter and soul are considered qualities of Brahman. This perspective highlights the interconnectedness of God, the material world, and individual souls.

Ramanujacharya’s Contributions: Ramanujacharya, a revered philosopher and theologian, made significant contributions to Vedantic literature. Among his notable works are:

- Sribhashya: A comprehensive commentary on the Brahma Sutras, offering deep insights into the foundational principles of Vedanta.

- Vedanta Dipa: An illuminating text shedding light on the intricate concepts of Vedanta, providing clarity to seekers of spiritual knowledge.

- Gita Bhasya: Ramanujacharya’s commentary on the Bhagavad Gita, offering a unique interpretation of Lord Krishna’s teachings in the context of Vishistadvaita philosophy.

- Vedantasara: A concise yet profound treatise encapsulating the essence of Vedanta, providing a concise guide to the philosophical tenets of Vishistadvaita.

Ramanujacharya’s writings not only elucidate the philosophical nuances of Vishistadvaita but also serve as foundational texts for scholars and practitioners seeking a deeper understanding of the relationship between the divine, the universe, and the individual soul. His works continue to be revered and studied in the realm of Vedantic philosophy.

Sivadvaita of Srikanthacharya

Sivadvaita, a philosophical system attributed to Srikanthacharya, posits that the ultimate reality, Brahman, is embodied in Shiva, along with Shakti, the divine feminine energy. According to this philosophy, Shiva exists not only in the transcendent realm but also within the world we inhabit. This belief underscores the omnipresence of Shiva, suggesting a divine presence both within the material world and beyond it, highlighting the interconnectedness of the spiritual and physical realms.

Dvaita of Madhavacharya:

- Dvaita, meaning dualism, contrasts sharply with the non-dualism and monism advocated by philosophers like Shankaracharya. Madhavacharya, the proponent of Dvaita, rejected the idea that the world is an illusion (maya). Instead, he asserted that the world is a tangible reality filled with distinct differences. In this worldview, the individual souls, the material world, and the divine are separate entities, each with their unique existence and characteristics.

Dvaitadvaita of Nimbaraka:

- Dvaitadvaita, often translated as dualistic monism, presents a nuanced perspective on the relationship between God, the world, and the individual soul. According to this philosophy, God transforms Himself into both the world and individual souls. While the world and souls are distinct from God (Brahman), they are intrinsically connected and dependent on Him for their existence. This dualistic monism acknowledges the separateness of the entities while emphasizing their interdependence on the divine support.

Suddhadvaita of Vallabhacharya:

- Vallabhacharya, a prominent philosopher, contributed to the development of Suddhadvaita, which translates to pure non-dualism. In this philosophical framework, Brahman, the ultimate reality, is understood as Sri Krishna, who manifests Himself as both souls and matter. Unlike the distinct separation seen in Dvaita, Suddhadvaita posits that God and the individual soul are not separate entities but are essentially one. The emphasis lies on the complete unity between God and the individual soul, underlining the concept of pure non-dualism.

Vallabhacharya’s philosophy, known as Pushtimarga or the path of grace, was instrumental in founding the Rudrasampradaya school of thought. This school emphasized the importance of divine grace and the inseparable unity of the individual soul with God, shaping the theological landscape within the broader context of Indian philosophy and spirituality.

| Philosophy | Key Tenets |

|---|---|

| Sivadvaita | – Ultimate Brahman is Shiva, endowed with Shakti. |

| – Shiva exists both within this world and beyond it. | |

| Dvaita | – Literal meaning of dvaita is dualism, opposed to non-dualism and monism. |

| – Belief in the reality of the world, rejecting it as an illusion (maya). | |

| Dvaitadvaita | – Dualistic monism where God transforms into the world and soul. |

| – World and soul are distinct from God (Brahman) but dependent on Him for survival. | |

| Suddhadvaita | – Brahman (God) is Sri Krishna, manifesting as souls and matter. |

| – God and soul are not separate entities but fundamentally one. | |

| – Emphasis on pure non-dualism. | |

| – Vallabhacharya’s philosophy known as Pushtimarga, focusing on divine grace. | |

| – School named Rudrasampradaya. |

Impact of the Bhakti-Sufi Movements on Indian Society

The Bhakti and Sufi movements in medieval India played a pivotal role in reshaping the social, religious, and cultural fabric of the country. Opposition to Bigotry and Rigidities marked these movements, promoting values of good character and pure thinking at a time when societal norms had become stagnant. Saints like Kabir and Nanak advocated for social equality, challenging established hierarchies and attracting the marginalized sections of society.

Cultural Renaissance and Language Evolution:

- The influence of these movements is evident in the cultural renaissance they ushered in. Bhakti and Sufi saints, being poets themselves, contributed significantly to regional literature. They wrote in local languages, breaking away from the confines of Persian. Amir Khusrau, a notable figure in this era, not only wrote verses in Hindi (Hindawi) but also created a new style called sabaq-i-hindi, blending Persian and Hindi elements. This interaction between languages and cultures gave rise to a distinct literary tradition.

Syncretism and Shared Terminologies:

- The interaction between Bhakti and Sufi saints led to an intriguing syncretism. Concepts such as Wahdat-al-Wujud (Unity of Being) in Sufism found similarities with ideas present in Hindu Upanishads. Sufi poets often used Hindi terms like Krishna, Radha, Gopi, and sacred rivers like Jamuna and Ganga, emphasizing shared cultural elements between the communities. This fusion was so profound that an eminent Sufi scholar, Mir Abdul Wahid, even penned a treatise explaining Islamic equivalents for these Hindu terms.

Musical Renaissance and Continuing Legacy:

- Furthermore, the devotional verses composed by these saints served as precursors to a musical renaissance. New musical compositions emerged, especially for group singing during kirtans and prayer meetings. Even in contemporary times, the bhajans of Mira and chaupais of Tulsidas continue to be recited, testifying to the enduring legacy of these movements in the Indian musical and spiritual traditions.

Influence on Rulers and Religious Policies:

- The impact of these movements extended to political spheres. Akbar’s liberal ideas, which sought to integrate diverse religious beliefs and foster tolerance, were influenced by the atmosphere created by these movements. The liberal religious policies of rulers like Akbar and Jahangir were informed by the spirit of inclusivity propagated by the Bhakti and Sufi saints.

In essence, the Bhakti and Sufi movements not only reshaped the religious landscape of medieval India but also fostered a cultural and literary richness that continues to influence the nation’s ethos to this day.

Table: Impact of Bhakti-Sufi Movements on Indian Society

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Opposition to Religious Bigotry and Rigidities | Bhakti and Sufi saints opposed religious intolerance and societal rigidities. They emphasized good character and pure thinking, revitalizing a stagnant society. |

| Redefined Social and Religious Values | Saints like Kabir and Nanak redefined social and religious values, advocating for egalitarianism. Their call for social equality resonated with the downtrodden, leading to social reordering. |

| Influence on Indian Culture and Literature | Bhakti and Sufi saints infused a liberal outlook in Hinduism and Islam, respectively. They contributed to a rich regional literature, writing in local languages such as Punjabi, Hindawi, and Bengali. |

| Impact on Language and Literature Evolution | Sufi saints like Baba Farid and Amir Khusrau wrote in regional languages, influencing the evolution of languages. The use of terms like Krishna and Radha became common, bridging cultural and linguistic gaps. |

| Influence on Rulers and Religious Policies | The atmosphere created by Bhakti and Sufi movements shaped the religious policies of rulers like Akbar and Jahangir. Their liberal ideas promoted religious tolerance and inclusivity, fostering an environment of cultural exchange. |