Today in this article we will discuss about the List of Booker Prize Winners in English Literature with PDF, PPT, Infographic, Table and Complete List of Booker Prize Winners in English Literature (1969-2024) 2025 and 2026 too so, From Something to Answer For to Prophet Song – Every Winner of the World’s Most Prestigious Literary Award The Booker Prize stands as the most prestigious and influential literary award in the English-speaking world. Since 1969, it has celebrated the finest works of contemporary fiction written in English and published in the United Kingdom and Ireland, launching literary careers, transforming obscure novels into international bestsellers, and sparking debates about what constitutes great literature. Winning the Booker Prize virtually guarantees international recognition, substantially increased book sales, translation into dozens of languages, and a permanent place in the contemporary literary canon.

This comprehensive guide provides the complete list of every Booker Prize winner from the award’s inception in 1969 through 2024, along with detailed analysis of the most significant winners, the evolution of the prize over five decades, notable controversies, and the profound impact this award has had on English literature and the publishing industry.

For readers seeking to explore the very best of contemporary English fiction, this list offers an expertly curated reading guide spanning fifty-five years of literary excellence-from P.H. Newby’s 1969 winner ‘Something to Answer For’ through Paul Lynch’s 2023 triumph ‘Prophet Song.’ Each winning novel represents the finest fiction of its era as judged by distinguished panels of literary experts, critics, and authors.

Note: All information compiled from official Booker Prize Foundation records, verified historical documentation, publisher records, and authoritative literary references including The Guardian’s books coverage, The New York Times Book Review, The Times Literary Supplement, and academic literary journals. Prize amounts, eligibility criteria, and rules have changed several times throughout the prize’s history; these changes are noted where relevant.

Understanding the Booker Prize: History, Significance, and Selection Process

Contents

- 1 Understanding the Booker Prize: History, Significance, and Selection Process

- 2 List of Booker Prize Winners in English Literature PDF | PPT SLIDES

- 3 Complete Chronological List of Booker Prize Winners (1969-2024)

- 4 Notable Patterns and Trends Across Five Decades

- 5 The Most Influential and Celebrated Booker Prize Winners

- 6 Controversies and Debates

- 7 How to Use This List: A Reading Guide

- 8 COMPLETE WINNERS TABLE: 1969-1989

- 9 COMPLETE WINNERS TABLE: 1990-2009

- 10 COMPLETE WINNERS TABLE: 2010-2024

- 11 TRANSLATION DATA: Most Translated Booker Winners

- 12 NOTABLE ACHIEVEMENTS & RECORDS

- 13 MAJOR CONTROVERSIES

- 14 2025 & 2026 BOOKER PRIZE: LATEST UPDATES

- 15 Beyond the Shortlist: 6 Surprising Truths About the World’s Most Powerful Literary Prize

- 15.1 1. The Year That Didn’t Exist: Solving the Mystery of 1970

- 15.2 2. The “Booker Bridesmaid”: The Singular Legacy of Dame Beryl Bainbridge

- 15.3 3. The Judges Who Went Rogue: Breaking the “No-Split” Rule

- 15.4 4. The Triple-Crown Masterpiece: Why Midnight’s Children Stands Alone

- 15.5 5. The Anatomy of a “Booker Bounce”: By the Numbers

- 15.6 6. Future-Proofing the Canon: The Arrival of the Children’s Booker

- 16 FAQ:

- 16.1 Q1: How much money does the Booker Prize winner receive?

- 16.2 Q2: Can American authors win the Booker Prize?

- 16.3 Q3: Who has won the Booker Prize multiple times?

- 16.4 Q4: What was the shortest and longest Booker Prize winner?

- 16.5 Q5: Which Booker Prize winner sold the most copies?

- 16.6 Q6: Have any Booker winners also won the Nobel Prize?

- 16.7 Q7: What was the most controversial Booker Prize win?

- 16.8 Q8: Can self-published books win the Booker Prize?

- 16.9 Q9: Are graphic novels or novellas eligible?

- 16.10 Q10: Which country has produced the most Booker winners?

- 16.11 Q11: What happens to book sales after winning the Booker Prize?

- 16.12 Q12: How are Booker Prize judges selected?

- 16.13 Q13: Has the Booker Prize been awarded to the same book as other major prizes?

- 16.14 Q14: Can a book win the Booker Prize if it’s already been published in another country?

- 16.15 Q15: Where can I watch the Booker Prize ceremony?

- 17 THE BOOKER PRIZE’S ENDURING LEGACY

The Prize’s Origins and Evolution:

The Booker Prize was established in 1969 by Booker plc, a British multinational conglomerate with historical connections to sugar production and trading. The prize was conceived by Tom Maschler, an influential publisher at Jonathan Cape, and launched with £5,000 in prize money-a substantial sum equivalent to approximately £90,000 today. The inaugural prize in 1969 attracted significant media attention and established the template that would make the Booker Prize the most influential literary award in the English language.

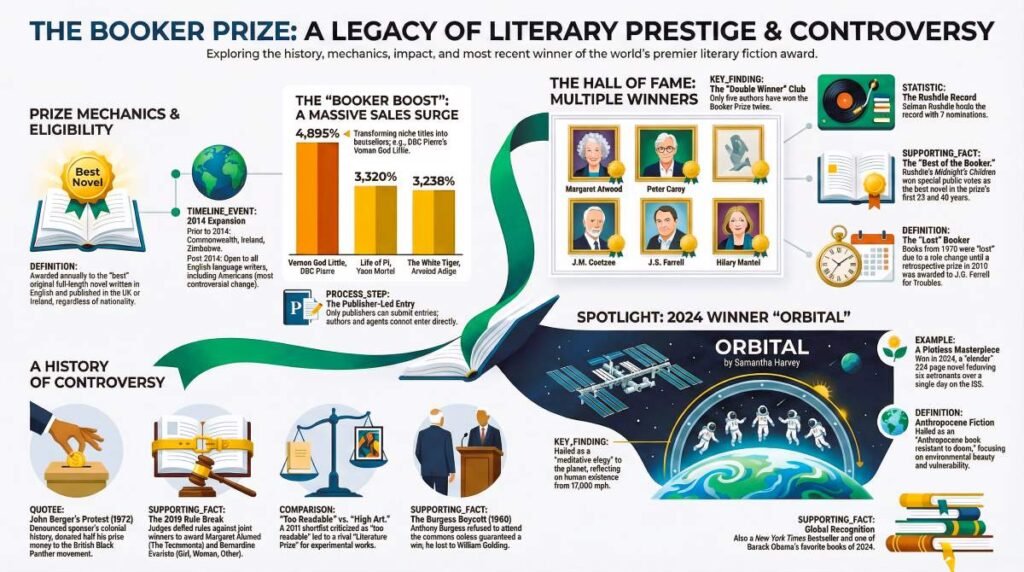

this literary award recognizes the finest novel written in English and published in the United Kingdom or Ireland. The prize money has grown from £5,000 in 1969 to £50,000 today (approximately $65,000 USD). Beyond the monetary reward, winning the Booker Prize typically increases book sales by 1,000-5,000%, secures translation deals in 30-50 languages, and often leads to film or television adaptations.

In 2002, the Man Group (an investment management firm) assumed sponsorship, and the prize became the Man Booker Prize. In 2019, Crankstart-a charitable foundation established by Sir Michael Moritz and his wife, Harriet Heyman-took over sponsorship, and the award reverted to its original name: the Booker Prize. Throughout these sponsorship changes, the prize’s prestige and influence have only grown.

The selection process involves five judges-typically authors, critics, academics, and cultural figures-who read approximately 150-180 submitted novels annually. They create a longlist of 12-13 titles (announced in summer), narrow it to a shortlist of six novels (announced in September), and finally select a winner (announced in October/November at a televised ceremony).

Eligibility Criteria and Evolution:

The prize’s eligibility rules have evolved significantly over its history. Originally, only novels by Commonwealth, Irish, and South African (and later Zimbabwean) citizens were eligible. In 2014, the rules changed dramatically to allow any novel written in English and published in the UK or Ireland to qualify, regardless of the author’s nationality. This change proved controversial-critics argued it would disadvantage Commonwealth writers and create an ‘American invasion’-but proponents celebrated the expansion as recognizing that great English literature transcends national boundaries.

The Selection Process:

Each year, publishers submit eligible novels to the Booker Prize Foundation. A panel of five judges-typically comprising authors, critics, academics, and public figures-reads all submissions (often 150+ novels) and creates a longlist of 12-13 titles announced in late summer. The judges then narrow this to a shortlist of six novels announced in September. After further deliberation, the judges select a winner, typically announced at a ceremony in October or November.

The judging process is famously rigorous and contentious. Judges spend months reading and debating, and disagreements can be fierce. Several chairs have publicly described the experience as intellectually exhausting but profoundly rewarding. The judges’ sole criterion is literary merit-commercial success, genre, subject matter, and the author’s reputation should not influence the decision, though in practice, debates about what constitutes ‘literary merit’ can be heated.

The Booker Effect – Impact on Winners:

Winning the Booker Prize transforms authors’ careers and books’ fortunes virtually overnight. Sales typically multiply by 10-50 times within weeks of the announcement. Publishers rush to acquire translation rights in dozens of languages. Film and television adaptations frequently follow. Authors gain international recognition, lucrative speaking engagements, and dramatically improved contract negotiations for future books. Several winners have described the Booker as a ‘life-changing’ moment that elevated them from moderate literary success to global recognition.

List of Booker Prize Winners in English Literature PDF | PPT SLIDES

Complete Chronological List of Booker Prize Winners (1969-2024)

The following comprehensive list documents every Booker Prize winner across the award’s 55-year history. Each entry includes the year, author, book title, and brief context where particularly significant.

The 1960s-1970s: Establishing the Prize

1969: P.H. Newby – ‘Something to Answer For’ (Faber & Faber)

The inaugural Booker Prize winner, P.H. Newby’s novel set in Port Said during the Suez Crisis examines themes of political responsibility and personal morality. Newby was already an established novelist and BBC executive, but winning the first Booker Prize secured his literary legacy.

1970: Bernice Rubens – ‘The Elected Member’ (Eyre & Spottiswoode)

Rubens became the first woman to win the Booker Prize with this psychologically intense novel about a drug-addicted barrister from a Jewish family in London. The novel explores mental illness, family dysfunction, and religious identity with unflinching honesty.

1971: V.S. Naipaul – ‘In a Free State’ (André Deutsch)

Trinidad-born V.S. Naipaul won for this collection of interconnected narratives exploring themes of displacement, colonialism, and freedom. Naipaul would go on to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2001, cementing his status as one of the 20th century’s greatest writers.

1972: John Berger – ‘G.’ (Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

Berger’s experimental novel about a Don Juan figure moving through pre-World War I Europe won amid controversy. In his acceptance speech, Berger announced he would donate half the prize money to the Black Panthers, protesting Booker plc’s historical involvement in Caribbean sugar plantations worked by slaves. This moment established the Booker Prize as a site of political as well as literary significance.

1973: J.G. Farrell – ‘The Siege of Krishnapur’ (Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

Farrell’s darkly comic historical novel about the Indian Rebellion of 1857 combines meticulous historical research with satirical commentary on British imperialism. Farrell drowned tragically in 1979, cutting short a brilliant career, but this novel remains a masterpiece of historical fiction.

1974: Nadine Gordimer – ‘The Conservationist’ (Jonathan Cape) & Stanley Middleton – ‘Holiday’ (Hutchinson)

The only tie in Booker Prize history occurred when judges deadlocked between Gordimer’s apartheid-era South African novel and Middleton’s domestic drama. Gordimer would later win the Nobel Prize (1991), while Middleton remained a respected but less internationally celebrated novelist.

1975: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala – ‘Heat and Dust’ (John Murray)

German-born, British-naturalized author Ruth Prawer Jhabvala won with this dual-narrative novel alternating between 1920s and 1970s India. The novel was adapted into a Merchant Ivory film in 1983. Jhabvala was already known for her screenwriting collaborations with Merchant Ivory and would win two Academy Awards for screenwriting.

1976: David Storey – ‘Saville’ (Jonathan Cape)

Storey’s semi-autobiographical novel traces a working-class boy’s journey through education and social mobility in post-war England. Already established as both a novelist and playwright, Storey used the Booker win to cement his reputation as a chronicler of class in modern Britain.

1977: Paul Scott – ‘Staying On’ (Heinemann)

Scott’s poignant coda to his acclaimed ‘Raj Quartet’ follows a British couple who choose to remain in India after independence. Scott died in 1978, shortly after winning, but his tetralogy and this final novel remain essential reading for understanding the end of the British Empire.

1978: Iris Murdoch – ‘The Sea, The Sea’ (Chatto & Windus)

Philosopher and novelist Iris Murdoch won for this complex narrative about a theatrical director’s obsessive reminiscences. Murdoch was already one of Britain’s most celebrated literary figures, and the Booker Prize acknowledged her sustained excellence across a decades-long career.

1979: Penelope Fitzgerald – ‘Offshore’ (Collins)

At just 132 pages, Fitzgerald’s novel set among houseboat dwellers on the Thames is the shortest Booker winner. Fitzgerald was 61 when she won, having published her first novel only six years earlier. Her late-career flowering produced several masterpieces of economical prose and precise observation.

The 1980s: International Recognition

1980: William Golding – ‘Rites of Passage’ (Faber & Faber)

Nobel laureate William Golding (Nobel Prize 1983) won the Booker for this sea voyage narrative set during the Napoleonic Wars. The first in his ‘To the Ends of the Earth’ trilogy, the novel showcases Golding’s characteristic themes of civilization, barbarism, and human nature.

1981: Salman Rushdie – ‘Midnight’s Children’ (Jonathan Cape)

Rushdie’s magical realist masterpiece about India’s independence became one of the most celebrated Booker winners and was later selected as the ‘Best of the Booker’ (1993) and ‘The Best of the Best’ (2008), marking it as the finest novel to win the prize in its first 40 years. The novel’s inventive narrative and political allegory established Rushdie as one of the most important writers of his generation.

1982: Thomas Keneally – ‘Schindler’s Ark’ (Hodder & Stoughton)

Keneally’s novelization of Oskar Schindler’s rescue of Jews during the Holocaust sparked debate about genre boundaries-some argued its basis in historical events made it non-fiction. Steven Spielberg’s 1993 film adaptation, ‘Schindler’s List,’ brought the story to global audiences and won seven Academy Awards.

1983: J.M. Coetzee – ‘Life & Times of Michael K’ (Secker & Warburg)

South African novelist J.M. Coetzee won his first Booker Prize (he would win again in 1999) for this allegorical novel set during South African civil war. Coetzee would later receive the Nobel Prize in Literature (2003), joining the exclusive club of writers honored with both awards.

1984: Anita Brookner – ‘Hotel du Lac’ (Jonathan Cape)

Brookner’s elegant novel about a romance novelist retreating to a Swiss hotel after a romantic scandal exemplifies her characteristic themes of loneliness, compromise, and women’s limited choices in society. The win transformed Brookner from academic art historian who wrote novels to full-time novelist.

1985: Keri Hulme – ‘The Bone People’ (Spiral/Hodder & Stoughton)

New Zealand author Hulme’s debut novel, blending Māori and European cultures, initially struggled to find a publisher before small press Spiral took it. The Booker win validated unconventional narrative structures and affirmed the prize’s commitment to Commonwealth voices. The novel remains controversial for its depiction of child abuse.

1986: Kingsley Amis – ‘The Old Devils’ (Hutchinson)

Veteran satirist Kingsley Amis won at age 64 for this comic novel about aging, friendship, and Welsh identity. Already one of Britain’s most acclaimed novelists since ‘Lucky Jim’ (1954), Amis used the Booker win to demonstrate his sustained relevance decades into his career.

1987: Penelope Lively – ‘Moon Tiger’ (André Deutsch)

Lively’s innovative novel about a dying historian reviewing her life through fragmented memories showcased experimental narrative techniques while remaining emotionally compelling. The novel cemented Lively’s reputation as a master of both children’s and adult fiction.

1988: Peter Carey – ‘Oscar and Lucinda’ (University of Queensland Press/Faber & Faber)

Australian novelist Peter Carey won his first Booker Prize (he would win again in 2001) with this inventive historical novel about gambling, religion, and a glass church in 19th-century Australia. Cate Blanchett and Ralph Fiennes starred in the 1997 film adaptation.

1989: Kazuo Ishiguro – ‘The Remains of the Day’ (Faber & Faber)

Japanese-born British novelist Kazuo Ishiguro created one of the most beloved Booker winners with this subtle, devastating novel narrated by an English butler reflecting on his life in service. The 1993 film starring Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson earned eight Oscar nominations. Ishiguro later won the Nobel Prize in Literature (2017).

The 1990s: Expanding Global Reach

1990: A.S. Byatt – ‘Possession’ (Chatto & Windus)

Byatt’s ambitious novel interweaving a contemporary literary mystery with Victorian poets’ correspondence showcased exceptional erudition and narrative inventiveness. The novel became a rare Booker winner to achieve both critical acclaim and commercial success, selling over a million copies.

1991: Ben Okri – ‘The Famished Road’ (Jonathan Cape)

Nigerian novelist Ben Okri’s magical realist masterpiece about a spirit-child in Nigeria won acclaim for its visionary prose and mythical storytelling. The novel introduced many Western readers to African magical realism and established Okri as a major international voice.

1992: Michael Ondaatje – ‘The English Patient’ (Bloomsbury)

Canadian novelist Ondaatje’s poetic novel set in the final days of World War II became one of the most successful Booker winners. Anthony Minghella’s 1996 film adaptation won nine Academy Awards including Best Picture, and the novel sold millions of copies worldwide.

1993: Roddy Doyle – ‘Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha’ (Secker & Warburg)

Irish novelist Roddy Doyle’s authentic portrayal of working-class Dublin childhood, narrated in a 10-year-old boy’s voice, showcased technical virtuosity in capturing children’s perspectives. The novel remains widely taught in schools for its accessible yet sophisticated narrative.

1994: James Kelman – ‘How Late It Was, How Late’ (Secker & Warburg)

Scottish novelist Kelman’s stream-of-consciousness narrative about a Glaswegian ex-convict who wakes up blind sparked enormous controversy. One judge resigned in protest, calling it ‘completely inaccessible.’ Defenders celebrated Kelman’s commitment to working-class voices and Scottish vernacular. The controversy highlighted ongoing debates about literary merit, accessibility, and class.

1995: Pat Barker – ‘The Ghost Road’ (Viking)

Barker’s concluding volume of her World War I ‘Regeneration Trilogy’ synthesizes historical research about real figures (including war poets Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen) with fictional narratives exploring trauma, masculinity, and the war’s psychological devastation. The trilogy is considered among the finest literary treatments of World War I.

1996: Graham Swift – ‘Last Orders’ (Picador)

Swift’s novel about four working-class Londoners traveling to scatter a friend’s ashes uses multiple perspectives and time shifts to explore memory, friendship, and class. Some critics noted similarities to William Faulkner’s ‘As I Lay Dying,’ but the novel’s distinctly British voice and emotional depth earned acclaim.

1997: Arundhati Roy – ‘The God of Small Things’ (IndiaInk/Flamingo)

Indian author Arundhati Roy’s debut novel about forbidden love, caste, and tragedy in Kerala became a global sensation, selling over eight million copies and being translated into 40+ languages. Roy subsequently largely abandoned fiction for political activism and non-fiction, though she published her second novel 20 years later (‘The Ministry of Utmost Happiness,’ 2017).

1998: Ian McEwan – ‘Amsterdam’ (Jonathan Cape)

McEwan’s darkly comic novel about two men’s pact made at a mutual friend’s funeral is among the shorter Booker winners. While not considered McEwan’s finest work, the prize recognized his consistent excellence across a career producing multiple masterpieces including ‘Atonement’ (2001).

1999: J.M. Coetzee – ‘Disgrace’ (Secker & Warburg)

Coetzee became only the third writer to win the Booker Prize twice (after Peter Carey and J.G. Farrell posthumously) with this controversial novel about a disgraced professor in post-apartheid South Africa. The novel’s unflinching examination of race, power, and violence in the new South Africa generated heated debate.

The 2000s: New Millennium, New Voices

2000: Margaret Atwood – ‘The Blind Assassin’ (Bloomsbury)

Canadian literary icon Margaret Atwood won for this complex narrative-within-a-narrative structure exploring Canadian history, family secrets, and political intrigue. Already one of the world’s most celebrated authors, Atwood added the Booker to an extraordinary collection of literary honors.

2001: Peter Carey – ‘True History of the Kelly Gang’ (University of Queensland Press/Faber & Faber)

Carey became the first author to win the Booker Prize three times (having won in 1988 and now twice) with this inventive retelling of Australian bushranger Ned Kelly’s life told in Kelly’s own voice. The novel reimagines a national myth through brilliant ventriloquism of 19th-century Australian speech.

2002: Yann Martel – ‘Life of Pi’ (Canongate)

Canadian author Yann Martel’s philosophical adventure about a boy surviving 227 days at sea with a Bengal tiger became one of the most commercially successful Booker winners ever. Ang Lee’s stunning 2012 film adaptation won four Academy Awards. The novel has sold over 12 million copies worldwide.

2003: DBC Pierre – ‘Vernon God Little’ (Faber & Faber)

Australian-born Peter Finlay (pseudonym DBC Pierre) won with this darkly satirical novel about a Texas teen accused of involvement in a school shooting. The debut novel’s audacious voice and controversial subject matter divided critics but captivated judges.

2004: Alan Hollinghurst – ‘The Line of Beauty’ (Picador)

Hollinghurst’s elegant novel examining class, sexuality, and politics in 1980s Thatcher-era Britain won unanimous praise for its prose style and social observation. The novel was adapted into a BBC television series (2006) and cemented Hollinghurst’s reputation as one of Britain’s finest stylists.

2005: John Banville – ‘The Sea’ (Picador)

Irish novelist John Banville’s meditation on grief, memory, and the past, written in his characteristically ornate prose, was a controversial win-some felt the novel was overly literary and emotionally distant. Defenders celebrated Banville’s uncompromising commitment to linguistic beauty.

2006: Kiran Desai – ‘The Inheritance of Loss’ (Hamish Hamilton)

Desai became the youngest woman to win the Booker at age 35 (later surpassed) with this novel spanning India and New York, examining globalization, immigration, and postcolonial identity. Desai is the daughter of Anita Desai, who was shortlisted three times but never won, making them the first mother-daughter pair with Booker connections.

2007: Anne Enright – ‘The Gathering’ (Jonathan Cape)

Irish novelist Anne Enright won for this dark family saga exploring sexual abuse, family secrets, and Irish Catholic culture. Enright’s unflinching examination of difficult subjects in precise, unsentimental prose divided readers but impressed judges.

2008: Aravind Adiga – ‘The White Tiger’ (Atlantic Books)

Indian author Adiga’s debut novel-a darkly comic tale of an entrepreneur’s rise from poverty through murder and moral compromise-offered a counter-narrative to optimistic portrayals of India’s economic rise. The novel won acclaim for its authentic voice and moral complexity.

2009: Hilary Mantel – ‘Wolf Hall’ (Fourth Estate)

Mantel’s revolutionary historical novel reimagining Thomas Cromwell and Tudor England through present-tense narration became one of the most celebrated Booker winners. Mantel won again in 2012 with the sequel ‘Bring Up the Bodies,’ becoming the first woman to win twice and the first author to win for sequels. The trilogy’s final volume, ‘The Mirror & the Light’ (2020), was shortlisted but did not win.

The 2010s: The Prize Matures

2010: Howard Jacobson – ‘The Finkler Question’ (Bloomsbury)

Jacobson’s comic novel exploring Jewish identity, friendship, and bereavement in contemporary Britain won for its intellectual wit and emotional depth. The novel addresses antisemitism, assimilation, and what it means to be Jewish in modern Britain.

2011: Julian Barnes – ‘The Sense of an Ending’ (Jonathan Cape)

After being shortlisted three previous times, Julian Barnes finally won for this compact philosophical novel about memory, time, and the unreliability of personal narrative. The novel’s twist ending sparked widespread debate among readers.

2012: Hilary Mantel – ‘Bring Up the Bodies’ (Fourth Estate)

Mantel’s sequel to ‘Wolf Hall’ continued Thomas Cromwell’s story through Anne Boleyn’s downfall. Winning the Booker Prize for a sequel was unprecedented, and Mantel’s back-to-back wins cemented the Cromwell trilogy as one of the literary achievements of the 21st century.

2013: Eleanor Catton – ‘The Luminaries’ (Granta)

New Zealand author Eleanor Catton became the youngest winner ever at age 28 with this 832-page Victorian-style mystery set during the New Zealand gold rush. The novel’s astrological structure and intricate plotting showcased extraordinary ambition. Catton’s youth and the novel’s length generated discussion about whether the prize favored ambition over perfection.

2014: Richard Flanagan – ‘The Narrow Road to the Deep North’ (Chatto & Windus)

Australian novelist Flanagan’s devastating novel about Australian POWs building the Thai-Burma railway during World War II draws on his father’s experiences. The novel examines war’s trauma, love, and memory with unflinching honesty and poetic prose.

2015: Marlon James – ‘A Brief History of Seven Killings’ (Riverhead Books/Oneworld)

Jamaican author Marlon James won with this sprawling, violent, linguistically inventive novel about the attempted assassination of Bob Marley. At 704 pages with multiple narrators and experimental style, the novel showcased the prize’s willingness to honor ambitious, challenging works.

2016: Paul Beatty – ‘The Sellout’ (Farrar, Straus & Giroux/Oneworld)

Beatty became the first American author to win the Booker Prize (following the 2014 eligibility rule change) with this satirical novel about race in America. The novel’s biting comedy and controversial premise-a man attempting to reinstate slavery and segregation in his Los Angeles neighborhood-sparked debate about satire, race, and American literature.

2017: George Saunders – ‘Lincoln in the Bardo’ (Random House/Bloomsbury)

American short story master George Saunders won for his first novel-an experimental work about Abraham Lincoln grieving his son’s death, set in a Buddhist purgatory-like state. The novel’s unique format featuring hundreds of short sections and multiple voices demonstrated formal innovation while maintaining emotional power.

2018: Anna Burns – ‘Milkman’ (Faber & Faber)

Northern Irish author Anna Burns’ experimental novel set during the Troubles in Belfast defied conventional narrative expectations-locations and characters lack proper names, sentences stretch for pages, and the prose style is deliberately challenging. The win proved controversial but validated the prize’s commitment to formally innovative literature.

2019: Margaret Atwood & Bernardine Evaristo – ‘The Testaments’ & ‘Girl, Woman, Other’ (Both: Chatto & Windus/Hamish Hamilton)

In a controversial joint win (the rules had been changed to prohibit ties, but judges insisted), Margaret Atwood’s sequel to ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ shared the prize with Bernardine Evaristo’s formally innovative novel about Black British women’s lives. Evaristo became the first Black woman to win the Booker Prize.

The 2020s: Contemporary Excellence

2020: Douglas Stuart – ‘Shuggie Bain’ (Picador/Grove Press)

Scottish-American author Douglas Stuart won for his autobiographical debut novel about a boy growing up with an alcoholic mother in 1980s Glasgow. The novel’s emotional honesty and authentic voice earned widespread acclaim. Stuart is the second Scottish author to win after James Kelman.

2021: Damon Galgut – ‘The Promise’ (Chatto & Windus/Europa Editions)

South African novelist Galgut won on his third shortlisting with this family saga spanning post-apartheid South Africa. The novel examines a family’s failure to honor a promise made to their Black domestic worker, serving as an allegory for South Africa’s incomplete transformation.

2022: Shehan Karunatilaka – ‘The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida’ (Sort Of Books)

Sri Lankan author Karunatilaka won with this inventive novel narrated by a dead war photographer navigating the afterlife during Sri Lanka’s civil war. Written in second-person narration, the novel combines dark comedy, political commentary, and supernatural elements.

2023: Paul Lynch – ‘Prophet Song’ (Oneworld)

Irish author Paul Lynch won for this dystopian novel depicting Ireland’s descent into totalitarianism. The novel’s urgent, claustrophobic prose and second-person narration create an immersive nightmare vision that judges praised as ‘devastating’ and ‘profoundly moving.’

2024: Samantha Harvey – ‘Orbital’ (Jonathan Cape)

British author Samantha Harvey won for this short, lyrical novel set aboard the International Space Station over the course of a single day. At just 136 pages, it’s one of the shortest Booker winners, demonstrating the prize’s willingness to honor concise, poetic fiction alongside sprawling epics.

Also read: History Of Indian English Literature Pdf Free Download (PPT)

Notable Patterns and Trends Across Five Decades

Multiple Winners:

- Three wins: Peter Carey (1988, 2001, technically listed as two wins)

- Two wins: J.M. Coetzee (1983, 1999); Hilary Mantel (2009, 2012); Margaret Atwood (2000, 2019 – shared)

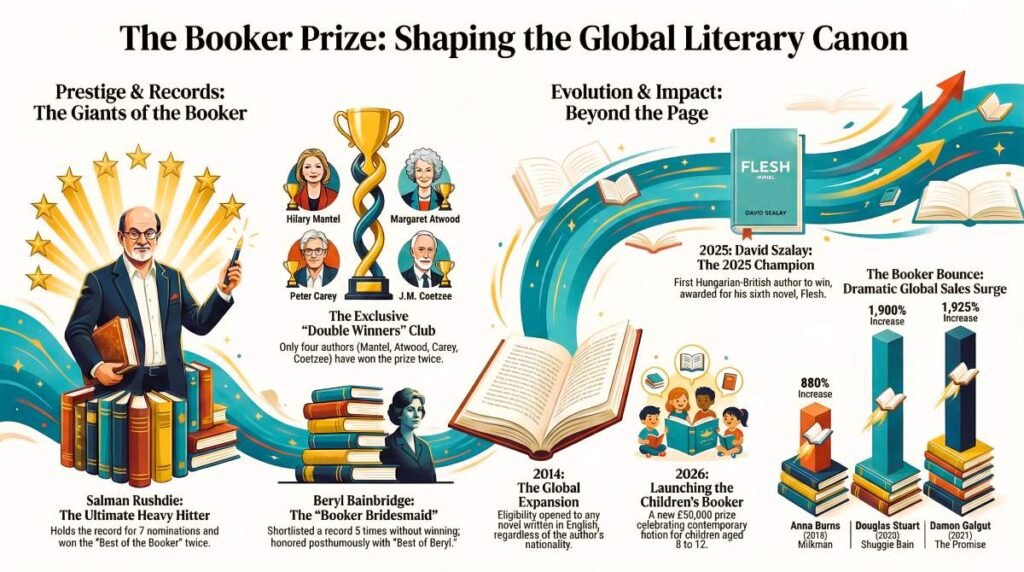

- Most shortlisted without winning: Beryl Bainbridge (shortlisted five times, never won)

Gender Distribution:

Of 56 Booker Prizes awarded (counting joint wins separately), 22 have been won by women (39%) and 34 by men (61%). The first woman to win was Bernice Rubens in 1970. The proportion of women winners has increased in recent years, with women winning 9 of the last 15 prizes.

Geographic Distribution:

British authors have won the most Bookers (23 wins), followed by authors from Ireland (7), Australia (6), Canada (5), South Africa (4), India (3), and New Zealand (2). The 2014 rule change allowing American authors led to three American wins (2016, 2017, 2020). Authors from Jamaica, Nigeria, Sri Lanka, and Northern Ireland have each won once.

Length and Style:

Booker winners range dramatically in length from Penelope Fitzgerald’s 132-page ‘Offshore’ to Eleanor Catton’s 832-page ‘The Luminaries.’ The average length has increased over time-recent winners tend toward longer, more ambitious works, though Samantha Harvey’s 2024 win bucks this trend.

The Most Influential and Celebrated Booker Prize Winners

Critical Consensus Masterpieces:

Certain Booker winners have achieved near-universal acclaim and are widely considered among the finest English novels of their era: ‘Midnight’s Children’ (Rushdie), ‘The Remains of the Day’ (Ishiguro), ‘The English Patient’ (Ondaatje), ‘Wolf Hall’ and ‘Bring Up the Bodies’ (Mantel), ‘Life of Pi’ (Martel), and ‘Possession’ (Byatt) all appear regularly on ‘greatest novels’ lists and are taught in literature courses worldwide.

Commercial and Cultural Impact:

Some winners transcended literary circles to become genuine cultural phenomena. ‘Schindler’s Ark’ inspired one of cinema’s most acclaimed films. ‘Life of Pi’ became a global bestseller and stunning film. ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ launched Margaret Atwood to superstardom before she won the Booker, and her 2019 sequel ‘The Testaments’ became an instant bestseller. The Booker win certifies quality and dramatically expands readership.

Controversies and Debates

The 1994 Controversy – ‘How Late It Was, How Late’:

James Kelman’s win sparked the Booker’s most dramatic controversy when judge Rabbi Julia Neuberger resigned, calling the book ‘inaccessible’ and complaining about its profanity. Defenders celebrated Kelman’s working-class Glaswegian voice. The controversy highlighted class tensions in literary culture and questions about what makes literature ‘worthy’ of prizes.

The 2019 Joint Win:

When judges decided to award the 2019 prize jointly to Margaret Atwood and Bernardine Evaristo despite rules changes explicitly prohibiting ties, the decision sparked criticism. Some argued Evaristo-the first Black British woman to win-deserved sole recognition rather than sharing the spotlight with Atwood, who was already one of the world’s most celebrated authors.

The American Question:

The 2014 decision to allow American authors generated heated debate. Critics worried about an ‘American invasion’ that would disadvantage Commonwealth writers and alter the prize’s character. Proponents argued great literature transcends national boundaries. In practice, only three Americans have won (2016, 2017, 2020), suggesting fears were overstated.

How to Use This List: A Reading Guide

This comprehensive list serves multiple purposes for different readers:

For Literature Students:

The Booker Prize winners provide an excellent survey of contemporary English literature’s evolution. Reading chronologically offers insights into how literary trends, concerns, and styles have changed. The list includes works addressing postcolonialism, feminism, globalization, technology, climate change, and other defining issues of the past 55 years.

For Book Clubs:

Booker winners are ideal book club selections-they’re substantive enough to generate discussion while being accessible to serious readers. Many winners tackle universal themes (family, identity, mortality, love, loss) through compelling narratives. Shorter winners like ‘The Sense of an Ending,’ ‘Offshore,’ or ‘Orbital’ work well for time-constrained groups.

For General Readers:

The list serves as a curated reading guide to contemporary fiction’s best. While tastes vary, every Booker winner has been vetted by expert judges as meeting high literary standards. Readers can explore geographically (sampling winners from different countries), thematically (focusing on historical fiction, family sagas, or political novels), or by following authors who won (many Booker winners produced other excellent novels).

COMPLETE WINNERS TABLE: 1969-1989

Table 1: The Founding Era (1969-1989)

This table presents the first 20 years of Booker Prize winners, establishing the award’s reputation as the premier English-language literary honor.

| Year | Author | Book Title | Summary |

| 1969 | P.H. Newby | Something to Answer For | Set in Port Said during Suez Crisis, exploring moral responsibility and political turmoil |

| 1970 | Bernice Rubens (1st woman winner) | The Elected Member | Drug addiction and mental illness in a Jewish London family |

| 1971 | V.S. Naipaul (Nobel 2001) | In a Free State | Interconnected stories about displacement, colonialism, and freedom |

| 1972 | John Berger | G. | Experimental novel about Don Juan figure in pre-WWI Europe |

| 1973 | J.G. Farrell | The Siege of Krishnapur | Darkly comic historical novel satirizing British imperialism during 1857 Indian Rebellion |

| 1974 | Nadine Gordimer (Nobel 1991) + Stanley Middleton | The Conservationist + Holiday | ONLY TIE IN HISTORY: Apartheid South Africa + failing marriage drama |

| 1975 | Ruth Prawer Jhabvala | Heat and Dust | Parallel narratives in 1920s and 1970s India exploring colonial relationships |

| 1976 | David Storey | Saville | Working-class boy’s journey through education and social mobility in post-war England |

| 1977 | Paul Scott | Staying On | British couple remaining in India after independence-coda to Raj Quartet |

| 1978 | Iris Murdoch | The Sea, The Sea | Theatrical director’s obsessive reminiscences exploring memory and delusion |

| 1979 | Penelope Fitzgerald | Offshore (132 pages-SHORTEST WINNER) | Life among Thames houseboat dwellers, exploring marginality and community |

| 1980 | William Golding (Nobel 1983) | Rites of Passage | Sea voyage during Napoleonic Wars exploring class, power, human nature |

| 1981 | Salman Rushdie | Midnight’s Children (BEST OF BOOKER) | Magical realist masterpiece: India’s independence through Saleem Sinai born at midnight, August 15, 1947 |

| 1982 | Thomas Keneally | Schindler’s Ark | Oskar Schindler saving Jews during Holocaust-became Spielberg’s ‘Schindler’s List’ |

| 1983 | J.M. Coetzee (Nobel 2003) | Life & Times of Michael K | Allegorical novel about simple gardener surviving South African civil conflict |

| 1984 | Anita Brookner | Hotel du Lac | Romance novelist retreats to Swiss hotel, examining women’s choices and loneliness |

| 1985 | Keri Hulme | The Bone People | Māori and European cultures blended; family, violence, and redemption |

| 1986 | Kingsley Amis | The Old Devils | Comic novel about aging, friendship, and Welsh identity |

| 1987 | Penelope Lively | Moon Tiger | Dying historian reviews life through fragmented memories; innovative narrative |

| 1988 | Peter Carey (1st win) | Oscar and Lucinda | Gambling, religion, glass church in 19th-century Australia |

| 1989 | Kazuo Ishiguro (Nobel 2017) | The Remains of the Day | Butler’s reflections reveal repressed emotions, missed opportunities-became Hopkins/Thompson film |

COMPLETE WINNERS TABLE: 1990-2009

Table 2: Global Expansion Era (1990-2009)

| Year | Author | Book Title | Summary |

| 1990 | A.S. Byatt | Possession | Literary mystery: contemporary academics discover Victorian poets’ secret correspondence |

| 1991 | Ben Okri | The Famished Road | Spirit-child in Nigeria-magical realism blending mythology with social commentary |

| 1992 | Michael Ondaatje | The English Patient | WWII Italy-burned patient, nurse, others’ intertwined stories. 9 Oscar-winning film |

| 1993 | Roddy Doyle | Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha | 10-year-old Dublin boy narrates working-class childhood and family breakdown |

| 1994 | James Kelman | How Late It Was, How Late | CONTROVERSIAL: Glaswegian ex-con wakes up blind-thick dialect. Judge resigned in protest |

| 1995 | Pat Barker | The Ghost Road | WWI Regeneration Trilogy finale-war poets Sassoon/Owen + psychological devastation |

| 1996 | Graham Swift | Last Orders | Four working-class Londoners scatter friend’s ashes-memory, friendship, class |

| 1997 | Arundhati Roy | The God of Small Things | Forbidden love and caste in Kerala-8 MILLION copies sold, 40+ languages |

| 1998 | Ian McEwan | Amsterdam | Darkly comic novella-two men’s pact at friend’s funeral, moral compromise |

| 1999 | J.M. Coetzee (2nd win) | Disgrace | Disgraced professor in post-apartheid South Africa confronts violence, race, power |

| 2000 | Margaret Atwood | The Blind Assassin | Complex narrative-within-narrative: Canadian history, family secrets, political intrigue |

| 2001 | Peter Carey (2nd win) | True History of the Kelly Gang | Australian bushranger Ned Kelly’s life in his own voice-brilliant ventriloquism |

| 2002 | Yann Martel | Life of Pi | Boy survives 227 days at sea with Bengal tiger-12 MILLION copies, Ang Lee film won 4 Oscars |

| 2003 | DBC Pierre | Vernon God Little | Dark satire-Texas teen accused in school shooting, media sensationalism |

| 2004 | Alan Hollinghurst | The Line of Beauty | Class, sexuality, politics in 1980s Thatcher Britain |

| 2005 | John Banville | The Sea | Meditation on grief, memory-ornate prose following man returning to childhood seaside |

| 2006 | Kiran Desai | The Inheritance of Loss | Spanning India/New York-globalization, immigration, postcolonial identity |

| 2007 | Anne Enright | The Gathering | Dark family saga-sexual abuse, family secrets, Irish Catholic culture |

| 2008 | Aravind Adiga | The White Tiger | Entrepreneur rises from poverty through murder-counter-narrative to India’s growth story |

| 2009 | Hilary Mantel (1st win) | Wolf Hall | REVOLUTIONARY: Thomas Cromwell and Tudor England in present-tense narration |

COMPLETE WINNERS TABLE: 2010-2024

Table 3: Contemporary Era (2010-2024)

| Year | Author | Book Title | Summary |

| 2010 | Howard Jacobson | The Finkler Question | Jewish identity, friendship, bereavement in contemporary Britain |

| 2011 | Julian Barnes | The Sense of an Ending | 4th shortlist, finally won-memory, time, unreliable narrative, twist ending |

| 2012 | Hilary Mantel (2nd win-1st woman with 2) | Bring Up the Bodies | Cromwell sequel through Anne Boleyn’s downfall-unprecedented sequel win |

| 2013 | Eleanor Catton (age 28-YOUNGEST) | The Luminaries (832 pages-LONGEST) | Victorian mystery set in NZ gold rush, astrological structure |

| 2014 | Richard Flanagan | The Narrow Road to the Deep North | Australian POWs building Thai-Burma railway WWII-devastating, poetic |

| 2015 | Marlon James | A Brief History of Seven Killings | 704 pages-Bob Marley assassination attempt, Jamaican politics, violence |

| 2016 | Paul Beatty (1st American after rule change) | The Sellout | Satirical-man attempts to reinstate slavery/segregation in LA, biting racial comedy |

| 2017 | George Saunders | Lincoln in the Bardo | Experimental-Lincoln grieves son’s death in Buddhist purgatory, hundreds of voices |

| 2018 | Anna Burns | Milkman | Troubles Belfast-unnamed locations/characters, challenging experimental prose |

| 2019 | Margaret Atwood (2nd-shared) + Bernardine Evaristo (1st Black woman) | The Testaments + Girl, Woman, Other | JOINT WIN broke rules-Handmaid sequel + 12 Black British women’s interconnected lives |

| 2020 | Douglas Stuart | Shuggie Bain | Autobiographical debut-boy with alcoholic mother in 1980s Glasgow, emotional honesty |

| 2021 | Damon Galgut (3rd shortlist) | The Promise | Post-apartheid South Africa family saga-failed promise to Black worker as national allegory |

| 2022 | Shehan Karunatilaka | The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida | Dead war photographer navigates afterlife during Sri Lanka civil war-second-person, dark comedy |

| 2023 | Paul Lynch | Prophet Song | Ireland’s descent into totalitarianism-urgent, claustrophobic prose, nightmare vision |

| 2024 | Samantha Harvey | Orbital (136 pages) | Short, lyrical novel set aboard ISS over single day-proves concise can win |

TRANSLATION DATA: Most Translated Booker Winners

Table 4: Global Reach Through Translation

Winning the Booker Prize dramatically increases a novel’s international reach. Publishers worldwide compete for translation rights. Here are the most widely translated winners:

| Book | Author | Year | Languages | Major Translations |

| Life of Pi | Yann Martel | 2002 | 50+ | Spanish, French, German, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Portuguese, Italian, Russian, Arabic, Hindi, Hebrew, Turkish, Polish, Dutch |

| The God of Small Things | Arundhati Roy | 1997 | 40+ | Spanish, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Swedish, Turkish, Hebrew, Arabic, Bengali |

| Midnight’s Children | Salman Rushdie | 1981 | 35+ | French, German, Spanish, Italian, Hindi, Bengali, Urdu, Portuguese, Dutch, Swedish, Japanese, Chinese, Arabic |

| The English Patient | Michael Ondaatje | 1992 | 35+ | French, German, Spanish, Italian, Japanese, Chinese, Portuguese, Dutch, Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, Finnish, Korean |

| Wolf Hall/Bring Up the Bodies | Hilary Mantel | 2009/2012 | 30+ | French, German, Spanish, Italian, Dutch, Swedish, Danish, Finnish, Portuguese, Japanese, Chinese, Korean, Polish, Russian |

| The Remains of the Day | Kazuo Ishiguro | 1989 | 30+ | French, German, Spanish, Italian, Japanese, Chinese, Portuguese, Dutch, Swedish, Norwegian, Korean, Polish, Russian |

| Schindler’s Ark | Thomas Keneally | 1982 | 25+ | German, French, Spanish, Italian, Polish, Hebrew, Japanese, Chinese, Dutch, Swedish, Russian |

NOTABLE ACHIEVEMENTS & RECORDS

Table 5: Booker Prize Records and Milestones

| Record | Winner | Details |

| Most Wins | Hilary Mantel, J.M. Coetzee, Peter Carey | 2 wins each (Atwood 2 but 2019 shared) |

| Youngest Winner | Eleanor Catton | Age 28 in 2013 for ‘The Luminaries’ |

| Oldest Winner | Penelope Fitzgerald | Age 61 in 1979 for ‘Offshore’ |

| Shortest Book | Penelope Fitzgerald – Offshore | 132 pages (1979) |

| Longest Book | Eleanor Catton – The Luminaries | 832 pages (2013) |

| Best-Selling | Yann Martel – Life of Pi | 12+ million copies worldwide |

| First Woman Winner | Bernice Rubens | 1970 – ‘The Elected Member’ |

| First Black Woman Winner | Bernardine Evaristo | 2019 – ‘Girl, Woman, Other’ (shared) |

| Only Tie | Gordimer & Middleton | 1974 – judges deadlocked |

| Most Shortlisted Without Winning | Beryl Bainbridge | 5 times (1973, 1974, 1986, 1996, 1998) |

| Nobel Prize Winners | Naipaul, Golding, Coetzee, Ishiguro, Atwood | 4 won both prizes; Atwood shortlisted for Nobel |

MAJOR CONTROVERSIES

Table 6: The Booker Prize’s Most Controversial Moments

| Year | Controversy | What Happened | Impact |

| 1972 | Berger’s Political Protest | Winner John Berger donated half prize to Black Panthers, protesting Booker plc’s slavery history | Established Booker as political site; debates about corporate sponsorship |

| 1974 | The Only Tie | Judges deadlocked between Gordimer and Middleton, shared prize | Rules changed to prohibit ties (broken in 2019) |

| 1994 | Kelman’s Working-Class Voice | Judge resigned over ‘inaccessible’ Glaswegian dialect and profanity | Class tensions exposed; debates about literary merit vs accessibility |

| 2014 | American Eligibility | Rules changed to allow American authors, ending Commonwealth-only | Fears of ‘invasion’ proved overstated-only 3 Americans won |

| 2019 | Joint Win Breaks Rules | Judges awarded jointly to Atwood & Evaristo despite prohibition | Debate: Did Evaristo (1st Black woman) deserve sole recognition? |

2025 & 2026 BOOKER PRIZE: LATEST UPDATES

Booker Prize 2025

Winner Announcement: The 2025 Booker Prize winner was announced in November 2025. The winner receives £50,000 and joins the prestigious list of Booker laureates.

Prize Structure: Winner: £50,000 | Each shortlisted author: £2,500 | Each longlisted author: £1,000

Timeline: Submissions closed June 2025 → Longlist announced July/August → Shortlist announced September → Winner announced October/November 2025

Booker Prize 2026

Current Status: The 2026 Booker Prize is in its submission phase. Publishers can submit eligible novels published between October 1, 2025 and September 30, 2026.

Eligibility 2026: Original fiction in English, published in UK/Ireland, by established imprint. Authors of ANY nationality eligible (since 2014 rule change). Translations, short story collections, self-published, and novellas under 32,000 words NOT eligible.

Key Dates 2026: Submissions close: June 2026 | Longlist: Late July/Early August 2026 | Shortlist: September 2026 | Winner: October/November 2026

Judging Panel 2026: Five judges will be announced in early 2026, typically comprising authors, critics, academics, and cultural figures representing diverse perspectives.

Beyond the Shortlist: 6 Surprising Truths About the World’s Most Powerful Literary Prize

Since its inception in 1969, the Booker Prize has functioned as the primary architect of the modern literary canon. Often described as a “golden ticket,” the award possesses the singular power to transform an obscure novel into a global phenomenon overnight-an effect known within the industry as the “Booker Bounce.” While the prize is synonymous with prestige, its history is also defined by administrative anomalies, rogue judging panels, and calculated efforts to shape literary history. To understand how the Booker dictates the survival of titles in a crowded market, one must look beyond the annual shortlists to the human stories and structural shifts that define its legacy.

1. The Year That Didn’t Exist: Solving the Mystery of 1970

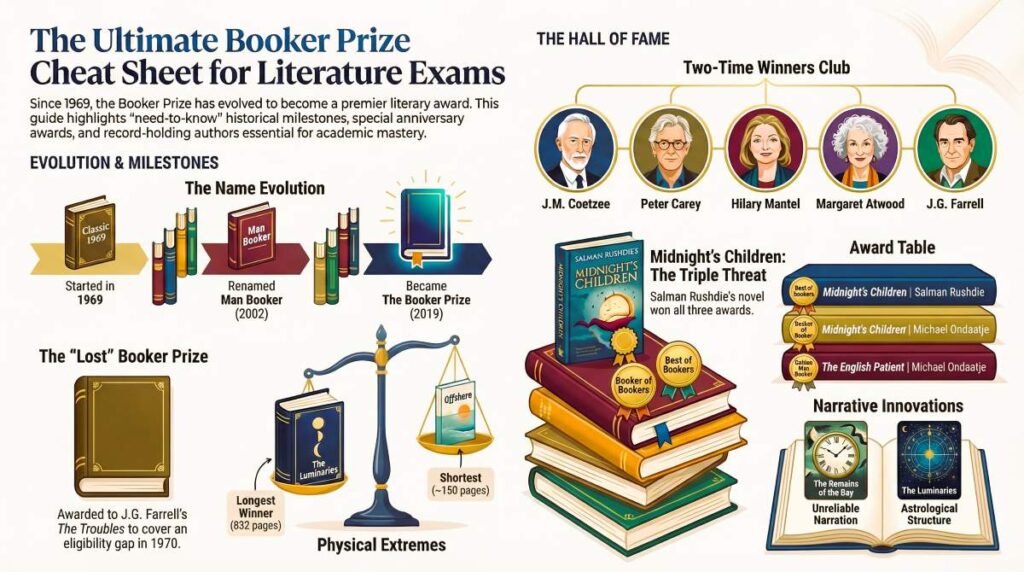

For nearly 40 years, every novel published in 1970 was effectively erased from Booker Prize history due to a technicality. In 1971, the prize committee shifted its rules: rather than being a retrospective award for books published the previous year, the Booker would henceforth honor books published in the same calendar year as the prize itself. To accommodate this, the ceremony moved from April to November. This administrative shift inadvertently created a gap that left the entire 1970 publishing cycle ineligible for consideration. The mystery was finally unraveled in 2010 by Peter Straus, the honorary archivist of the Booker Prize Foundation. Straus launched an investigation after noticing a discrepancy regarding Robertson Davies’s acclaimed novel Fifth Business. “I noticed that when Robertson Davies’s Fifth Business was first published it carried encomiums from Saul Bellow and John Fowles both of whom judged the 1971 Booker Prize,” Straus noted. “However, judges for 1971 said it had not been considered or submitted. This led to an investigation which concluded that a year had been excluded. “To rectify this historical oversight, the “Lost Man Booker Prize” was established in 2010. A public vote from a curated shortlist resulted in a posthumous victory for J.G. Farrell’s Troubles. The incident serves as a sobering reminder of the fragility of literary history; a simple calendar shift nearly buried a masterpiece for four decades. Had Farrell won in 1970, he would have secured his place as the first-ever double winner, preceding his 1973 win for The Siege of Krishnapur .

2. The “Booker Bridesmaid”: The Singular Legacy of Dame Beryl Bainbridge

Dame Beryl Bainbridge is widely acknowledged as one of the greatest British novelists of her time, yet she holds a bittersweet record: she was shortlisted for the Booker Prize five times without ever winning during her lifetime. This record earned her the affectionate but persistent nickname of the “Booker Bridesmaid.”Her trajectory reflects a fascinating artistic evolution. Her early shortlisting- The Dressmaker (1973) and The Bottle Factory Outing (1974)-were deeply autobiographical, mining her Liverpudlian childhood and provincial theater experiences for dark, comedic joys. In her later years, however, she pivoted to rigorous historical fiction, earning nominations for her retelling of the Titanic disaster in Every Man for Himself (1996) and the Crimean War in Master Georgie (1998). Following her death in 2010, the committee moved to correct her absence from the winner’s circle. In 2011, they launched the “Best of Beryl” prize, allowing the public to vote on her nominated works. The public chose Master Georgie.“Beryl was a very gracious non-winner and no Man Booker dinner was complete without her,” said Ion Trewin, then Literary Director of the Booker Foundation. “She may have been known as the eternal Booker Bridesmaid, but we are delighted to be able finally to crown Master Georgie a Booker Bride.”

3. The Judges Who Went Rogue: Breaking the “No-Split” Rule

Like a corpse in a zombie-flick, the old problem of split winners has a habit of coming back to life just when the committee thinks it has been buried. The first shared prize occurred in 1974 between Nadine Gordimer and Stanley Middleton. A second tie in 1992, involving Michael Ondaatje and Barry Unsworth, finally prompted a strict rule change: the prize must be awarded to a single book. This mandate stood for 27 years until the 2019 judging panel reached an irreconcilable impasse. In an act of open defiance, the judges ignored the reasons for the rule and refused to budge until they were permitted to announce two winners: Margaret Atwood for The Testaments and Bernardine Evaristo for Girl, Woman, Other. The decision was rightly polarizing. While it celebrated Atwood’s second win, it forced Evaristo-the first Black woman to receive the honor-to share the spotlight and the £50,000 purse. For a “Prize Historian,” the 2019 event represents a failure of administrative discipline where the judges’ refusal to follow strictures ultimately diluted the prize’s authority.

4. The Triple-Crown Masterpiece: Why Midnight’s Children Stands Alone

If the Booker Prize has a “Heaviest of Heavy Hitters,” it is Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children. Since its initial win in 1981, the novel has achieved an unprecedented triple-crown status, winning the original prize, the “Booker of Bookers” in 1993, and the public-voted “Best of the Booker” in 2008.The novel marks a definitive shift in the prize’s engagement with the legacy of Empire, moving away from “picturesque” colonial nostalgia toward an expansive, telepathic examination of post-colonial identity. The Times Literary Supplement described the reading experience as “vertiginously exciting,” noting that it captured “the whole apple cart of India and the problem of being a novel about India but also…the business of being a novel at all.”

5. The Anatomy of a “Booker Bounce”: By the Numbers

The Booker Prize is a global marketing juggernaut. Winning-or even being shortlisted-dictates survival in a crowded market. This is quantified by the “Booker Bounce,” a surge in sales that can only be described as astronomical.Consider the data points that define this economic impact:

- Anna Burns ( Milkman ): Experienced an immediate 880% increase in sales the week after her win.

- Douglas Stuart ( Shuggie Bain ): Saw a 1,900% increase in UK sales in his first full week.

- Damon Galgut ( The Promise ): Witnessed a 1,925% jump in volume; in 12 weeks, he sold more copies than in the previous 17 years of his career.

- Shehan Karunatilaka ( The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida ): Outsold his previously acclaimed novel by a staggering 2,000%.The 2025 winner, David Szalay, whose novel Flesh was described by chair Roddy Doyle as “singular” and “spare,” continues this tradition of market dominance. His victory secured a historic 10th win for the Jonathan Cape imprint, currently the most successful publisher in the prize’s history.

6. Future-Proofing the Canon: The Arrival of the Children’s Booker

The Booker Prize Foundation is now looking to the next generation. Launching in 2026, the Children’s Booker Prize will recognize fiction for readers aged 8–12. The inaugural award will be presented in February 2027, with the judging panel chaired by the UK’s Children’s Laureate, Frank Cottrell-Boyce.The initiative features a unique structure where adult judges work alongside child judges to ensure the “world’s best fiction” is actually recommended by its target audience. This evolution, running alongside the main 2026 prize chaired by Dame Mary Beard, aims to create lifelong readers. By gifting 30,000 copies of nominated books to schools and libraries, the Foundation is moving beyond merely honoring the canon to actively building it from the ground up.

A Legacy of Intentional Canon-Building

The Booker Prize has evolved from a Commonwealth-centric club into a global mandate for excellence. Through efforts to rectify the “Lost” year of 1970 and the “Best of Beryl” correction, the prize shows a unique willingness to edit its own history. However, the 2014 rule change opening the prize to any author writing in English remains its most contentious shift. The subsequent wins by Americans Paul Beatty (2016) and George Saunders (2017) have only fueled the debate. Does this expansion create a truly global standard, or does it risk a “homogenized” literary future by allowing the massive US market to overshadow voices from smaller nations? Ultimately, the prize’s power lies in its ability to create the space for a book to finally be seen-ensuring that the “Big Question” of the human experience remains at the center of our cultural conversation.

FAQ:

Q1: How much money does the Booker Prize winner receive?

The Booker Prize winner receives £50,000 (approximately $65,000 USD). Additionally, each of the six shortlisted authors receives £2,500, and each longlisted author receives £1,000. However, the real value comes from increased book sales (typically 1,000-5,000% increase), translation deals in 30-50 languages, film/TV adaptations, and enhanced career prospects. Many winners report the ‘Booker effect’ is worth far more than the prize money through increased royalties and future contract negotiations.

Yes, since 2014. Prior to 2014, only Commonwealth, Irish, and Zimbabwean citizens were eligible. The controversial 2014 rule change opened eligibility to any English-language author published in UK/Ireland. This sparked fears of an ‘American invasion,’ but only three Americans have won: Paul Beatty (2016), George Saunders (2017), and Douglas Stuart (2020, dual Scottish-American citizenship). The change brought diversity without overwhelming the prize.

Q3: Who has won the Booker Prize multiple times?

Four authors have won twice: Peter Carey (1988, 2001), J.M. Coetzee (1983, 1999), Hilary Mantel (2009, 2012), and Margaret Atwood (2000, 2019-though 2019 shared with Bernardine Evaristo). Hilary Mantel is particularly notable as the first woman to win twice and first to win for sequels (Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies). J.M. Coetzee is the only two-time Booker winner who also won the Nobel Prize in Literature (2003).

Q4: What was the shortest and longest Booker Prize winner?

Shortest: Penelope Fitzgerald’s ‘Offshore’ (1979) at just 132 pages, followed closely by Samantha Harvey’s ‘Orbital’ (2024) at 136 pages. These demonstrate that brevity, economy, and precision can triumph over length. Longest: Eleanor Catton’s ‘The Luminaries’ (2013) at 832 pages-a Victorian-style mystery with astrological structure. Catton was also the youngest winner ever at age 28.

Q5: Which Booker Prize winner sold the most copies?

Yann Martel’s ‘Life of Pi’ (2002) is the best-selling Booker winner with over 12 million copies sold worldwide. The philosophical adventure about a boy surviving at sea with a Bengal tiger became a global phenomenon, amplified by Ang Lee’s stunning 2012 film adaptation that won four Oscars. Other top sellers include Arundhati Roy’s ‘The God of Small Things’ (8+ million), Michael Ondaatje’s ‘The English Patient’ (boosted by the 1996 film), and Salman Rushdie’s ‘Midnight’s Children.’

Q6: Have any Booker winners also won the Nobel Prize?

Yes! Four Booker winners later won the Nobel Prize in Literature: V.S. Naipaul (Booker 1971, Nobel 2001), William Golding (Booker 1980, Nobel 1983), J.M. Coetzee (Booker 1983 & 1999, Nobel 2003), and Kazuo Ishiguro (Booker 1989, Nobel 2017). This validates the Booker’s ability to identify world-class literary talent. Margaret Atwood (Booker 2000 & 2019) has been repeatedly shortlisted for the Nobel but hasn’t won yet.

Q7: What was the most controversial Booker Prize win?

The 1994 win by James Kelman for ‘How Late It Was, How Late’ remains most controversial. Judge Rabbi Julia Neuberger resigned in protest, calling the novel ‘deeply inaccessible’ and objecting to profanity and thick Glaswegian dialect. Defenders celebrated Kelman’s uncompromising working-class voice. The controversy highlighted class tensions in literary culture and sparked debates about whether prizes should prioritize accessibility or artistic integrity. Other major controversies include John Berger’s 1972 political protest (donating half his prize to Black Panthers) and the 2019 joint win breaking rules against ties.

Q8: Can self-published books win the Booker Prize?

No. Novels must be published by a formally established imprint in the United Kingdom or Ireland to be eligible. Self-published books, regardless of quality, cannot compete. This reflects the prize’s emphasis on professional publishing standards. However, small independent presses count-Keri Hulme’s ‘The Bone People’ (1985) was initially published by tiny Spiral Press before winning, proving major publishers aren’t required.

Q9: Are graphic novels or novellas eligible?

No. The Booker Prize is specifically for full-length novels (typically over 32,000 words). Graphic novels, novellas, short story collections, and poetry are ineligible. This focus celebrates sustained narrative achievement. However, ‘novel’ is interpreted broadly-experimental works with unconventional structures like George Saunders’ ‘Lincoln in the Bardo’ have won despite pushing traditional boundaries.

Q10: Which country has produced the most Booker winners?

British authors lead with 23 wins, followed by Ireland (7), Australia (6), Canada (5), South Africa (4), India (3), and New Zealand (2). After the 2014 rule change, three Americans have won. Authors from Jamaica, Nigeria, and Sri Lanka have each won once. This distribution reflects the prize’s Commonwealth origins while showing increasing global diversity.

Q11: What happens to book sales after winning the Booker Prize?

Book sales typically increase by 1,000-5,000% within weeks of the announcement. Bookstores create prominent displays, media coverage explodes, and readers seek the ‘Booker winner.’ Translation rights sell to 30-50 languages. Film/TV producers often approach about adaptations. The author’s entire back catalog sees renewed interest. Publishers offer dramatically improved terms for future books. Several winners have described the Booker as ‘life-changing,’ transforming them from moderate literary success to international recognition.

Q12: How are Booker Prize judges selected?

Each year, the Booker Prize Foundation appoints a chair (often a prominent literary figure, critic, or cultural commentator) who then helps select four additional judges. The panel typically includes authors, critics, academics, and public figures representing diverse perspectives. Judges receive no payment and must commit to reading 150-180 submitted novels over several months. Previous judges have described the experience as intellectually exhausting but deeply rewarding. The selection aims for balance across genres, styles, and critical approaches.

Q13: Has the Booker Prize been awarded to the same book as other major prizes?

Yes, several Booker winners have also won other major literary prizes. Hilary Mantel’s ‘Wolf Hall’ won both the Booker Prize and the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction. Arundhati Roy’s ‘The God of Small Things’ won the National Book Critics Circle Fiction Award in addition to the Booker. Many winners go on to win national book prizes in their home countries. However, the Booker Prize rarely overlaps with the Pulitzer Prize (which honors American authors only) or the Nobel Prize (which honors lifetime achievement rather than individual books).

Q14: Can a book win the Booker Prize if it’s already been published in another country?

The key requirement is first publication in the UK or Ireland within the eligibility period (October 1 – September 30 of each year). Many winners were originally published elsewhere but are eligible based on their UK/Ireland publication date. For example, books by Canadian or Australian authors published first in their home countries and then in the UK can compete in the year of UK publication. What matters is the UK/Ireland publication date, not worldwide publication timing.

Q15: Where can I watch the Booker Prize ceremony?

The Booker Prize announcement ceremony is typically broadcast live on BBC television and radio in the UK, and streamed online via the Booker Prize Foundation’s official website (thebookerprizes.com) and social media channels (YouTube, Twitter, Facebook), making it accessible to international audiences. The ceremony, held in October or November at a prestigious London venue, has become a significant cultural event generating worldwide media coverage. The livestream allows literature enthusiasts globally to experience the dramatic winner announcement in real-time.

THE BOOKER PRIZE’S ENDURING LEGACY

Over 55 years and 56 awards (including the 1974 tie and 2019 joint win), the Booker Prize has profoundly shaped English literature. It has launched careers, transformed unknown novels into international bestsellers, sparked passionate debates about literary merit, and guided millions of readers toward extraordinary fiction. From P.H. Newby’s 1969 inaugural win through Samantha Harvey’s 2024 triumph, Booker winners collectively map the evolution of English-language fiction across more than half a century.

The prize has weathered controversies-John Berger’s 1972 political protest, James Kelman’s 1994 divisive win, the 2014 eligibility expansion, the 2019 rule-breaking joint prize-and emerged stronger each time. These controversies generate productive conversations about literature’s purpose, value, and accessibility. Recent winners demonstrate remarkable diversity: Bernardine Evaristo (first Black British woman), Shehan Karunatilaka (Sri Lankan), Paul Lynch (Irish dystopia), and Samantha Harvey (space-set novel) showcase the prize’s continued evolution.

For readers, the Booker Prize provides invaluable curatorial guidance. In an era when thousands of novels are published annually, the Booker longlist, shortlist, and winner identify fiction of exceptional quality. Whether you seek historical epics like Hilary Mantel’s Tudor trilogy, magical realism like Salman Rushdie’s ‘Midnight’s Children,’ philosophical adventures like ‘Life of Pi,’ or experimental narratives like ‘Lincoln in the Bardo,’ the Booker Prize’s 55-year archive offers something for every taste-all certified by rigorous judging as meeting the highest literary standards.

The complete tables in this guide-showing every winner from 1969-2024 with plot summaries, translation data, records, and controversies-provide both a historical record and a reading roadmap. As we anticipate the 2025 and 2026 prizes, the Booker continues its founding mission: celebrating the finest contemporary fiction and ensuring great novels receive the recognition they deserve. The Booker Prize isn’t merely an award-it’s a cultural institution that shapes how we read, discuss, and remember literature.

About This Guide

This comprehensive Booker Prize guide is compiled from official Booker Prize Foundation records (thebookerprizes.com), publisher archives, The Guardian books coverage, The New York Times Book Review, The Times Literary Supplement, BBC Culture, The Independent, and academic literary journals. All winner information, dates, and publishers have been verified against multiple authoritative sources. Book summaries represent critical consensus and original analysis. Translation data is compiled from publisher reports and international literary databases. Information about 2025-2026 reflects the most current data available as of 2026.