Today in this article we will discuss about the History of Indian English Literature Pdf Free Download (ppt), History of Indian English Literature with PDF, Inforagphic and PPT Slides: A Complete Guide from Colonial Roots to Modern Masters and we will Explore the rich and fascinating history of Indian English literature – from its colonial beginnings in the 18th century to Booker Prize-winning authors of today. A comprehensive guide covering key authors, movements, and milestones.

Why Indian English Literature Matters?

Contents

- 1 Why Indian English Literature Matters?

- 2 History Of Indian English Literature Pdf Free Download (PPT SLIDES)

- 2.1 #1. The Colonial Beginnings: 18th and Early 19th Century

- 2.2 #2. The Nationalist Era: Late 19th to Early 20th Century

- 2.3 #3. The Pre-Independence Novel: The 1930s and 1940s

- 2.4 #4. Post-Independence Literature: 1947 to the 1980s

- 2.5 #5. The Rushdie Revolution: 1981 and Its Aftermath

- 2.6 #6. The 1980s and 1990s: A Literary Renaissance

- 2.7 #7. Indian Diaspora Literature: Writing Between Worlds

- 2.8 #8. Contemporary Indian English Literature: The 21st Century

- 2.9 #9. Indian English Poetry: A Tradition of Its Own

- 2.10 #10. Indian English Drama: The Overlooked Genre

- 2.11 #11. Key Themes in Indian English Literature

- 2.12 #12. Awards, Recognition, and Global Impact

- 2.13 #13. The Digital Age and the Future of Indian English Literature

- 3 Beyond the Canon: 6 Surprising Takeaways That Redefined Indian Literature

- 3.1 I. The Stories We Thought We Knew

- 3.2 1. The Immigrant Who “Discovered” England: Dean Mahomed

- 3.3 2. Ancient Fluidity vs. Colonial Chains: The Queer Literary Thread

- 3.4 3. The “Big Three” and the Architecture of Modern Identity

- 3.5 4. Girish Karnad: Using 14th-Century Sultans to Critique the Present

- 3.6 5. Tagore’s “Educational Rebellion” and the Global Short Story

- 3.7 6. Badal Sircar and the “Third Theatre” Revolution

- 3.8 The Power of the Reclaimed Narrative

- 3.9 Conclusion: A Literature of Extraordinary Vitality

- 4 Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

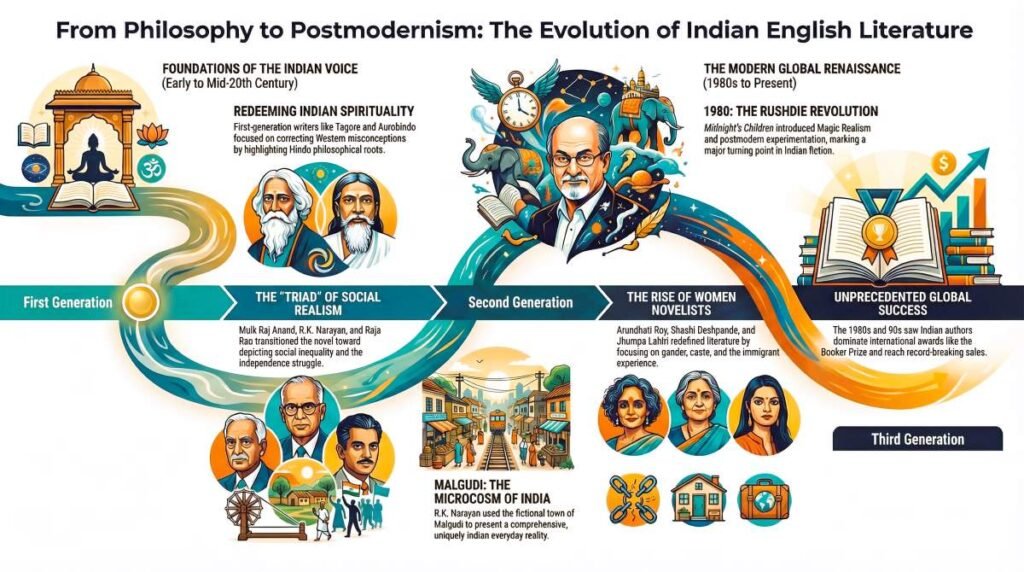

When we talk about world literature in English, few traditions are as layered, as politically charged, or as culturally vibrant as Indian English literature. Born out of the complex encounter between colonialism and one of the world’s oldest civilizations, this literary tradition has grown into a global force – giving us writers like Rabindranath Tagore, R.K. Narayan, Salman Rushdie, Arundhati Roy, and Jhumpa Lahiri, whose works have shaped how the world reads and thinks about India.

But what exactly is Indian English literature? At its core, it refers to works written in the English language by authors of Indian origin or nationality – whether they live in India or the diaspora. It is a literature that wrestles constantly with questions of identity, belonging, history, language, and the colonial past. It is a literature that refuses easy definitions.

This article offers a thorough, chronological, and thematic journey through the history of Indian English literature – covering its origins, its major periods, its landmark texts, its celebrated authors, and its place in the global literary conversation today.

History Of Indian English Literature Pdf Free Download (PPT SLIDES)

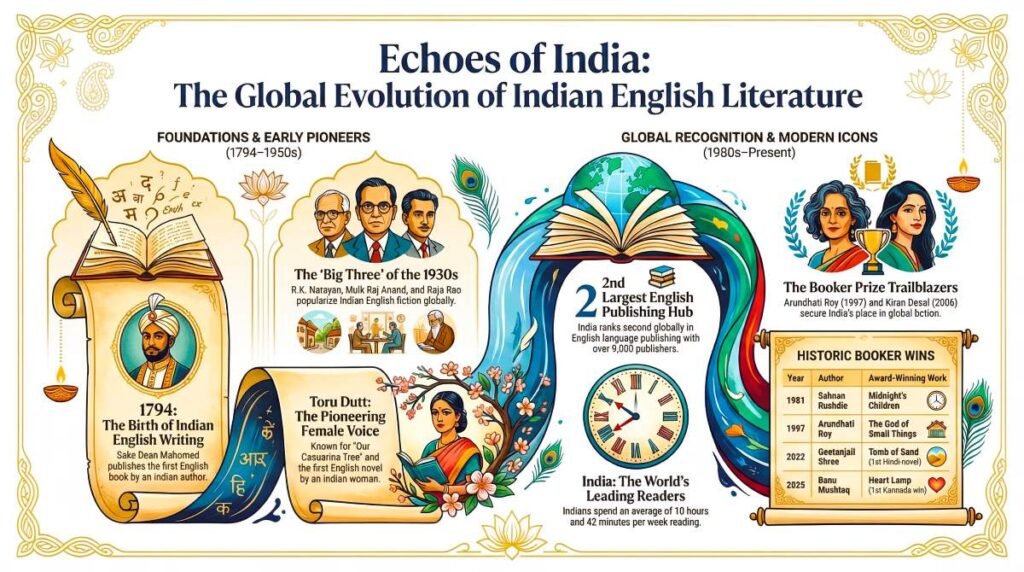

#1. The Colonial Beginnings: 18th and Early 19th Century

The Arrival of English in India: The story of Indian writing in English cannot be told without understanding the political context in which English first arrived on Indian soil. The British East India Company established trading posts in the early 17th century, and by the mid-18th century, the British Crown had begun consolidating political control over the subcontinent. With this control came the English language – as a tool of administration, commerce, and, eventually, cultural domination.

The decisive moment came in 1835, when Thomas Babington Macaulay introduced his infamous “Minute on Indian Education,” arguing that the British should create “a class of persons, Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect.” This colonial policy made English the medium of higher education in India and, paradoxically, laid the foundation for a distinctly Indian literary voice in English.

Early Indian Writers in English: The earliest Indian attempts at English writing were often closely tied to political and social reform. Writers of this era were, in many ways, navigating a double consciousness – they were educated in the colonial language but deeply committed to their own cultural and social contexts.

- Henry Louis Vivian Derozio (1809–1831) is often considered the first significant Indian poet to write in English. A teacher at Hindu College in Calcutta and a radical thinker, Derozio wrote poetry that blended Romantic influences with an emerging Indian sensibility. His poem To India – My Native Land is a landmark work, expressing a passionate love for the motherland combined with a grief over her subjugated condition. Though he died tragically young at 22, Derozio’s influence on the so-called “Young Bengal” intellectual movement was enormous.

- Kasiprasad Ghosh published The Shair and Other Poems in 1830, making it one of the earliest collections of poetry by an Indian author in English.

- Rabindranath Tagore – though primarily a Bengali writer – deserves mention here as a transitional figure of towering importance. When his collection Gitanjali (Song Offerings) was translated into English and published in 1912, it caused a sensation in the literary world. In 1913, Tagore became the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. While Tagore’s original compositions were in Bengali, his English translations (often done by himself) introduced Indian philosophical and spiritual thought to a global English-reading audience and gave Indian writing its first place on the world stage.

#2. The Nationalist Era: Late 19th to Early 20th Century

Literature as a Tool of Resistance: As the Indian nationalist movement gathered momentum through the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Indian English literature began to take on a more explicitly political character. Writers used the colonial language itself as a weapon against colonial power – a deeply ironic and subversive gesture that would define much of the tradition going forward.

- Romesh Chunder Dutt (1848–1909) wrote historical novels in English – The Lake of Palms (1902) and The Slave Girl of Agra (1909) – that reconstructed Indian history and presented Indians as dignified, complex human beings rather than colonial subjects. His economic writings, particularly The Economic History of India, also had a major impact on nationalist economic thought.

- Sarojini Naidu (1879–1949), known as the “Nightingale of India,” wrote luminous poetry in English that celebrated Indian landscapes, festivals, and people. Her collections – The Golden Threshold (1905), The Bird of Time (1912), and The Broken Wing (1917) – brought an intensely lyrical, distinctly Indian voice to English verse. Naidu was also a prominent figure in the Indian National Congress and a close associate of Mahatma Gandhi, and her poetry always carried a current of political awareness.

- Aurobindo Ghosh (Sri Aurobindo, 1872–1950) wrote extensively in English – poetry, plays, philosophical essays, and his monumental epic poem Savitri (1950), which runs to over 23,000 lines and is considered one of the longest poems in the English language. His English writings blended Indian spiritual philosophy with European literary forms in a way that was entirely unprecedented.

#3. The Pre-Independence Novel: The 1930s and 1940s

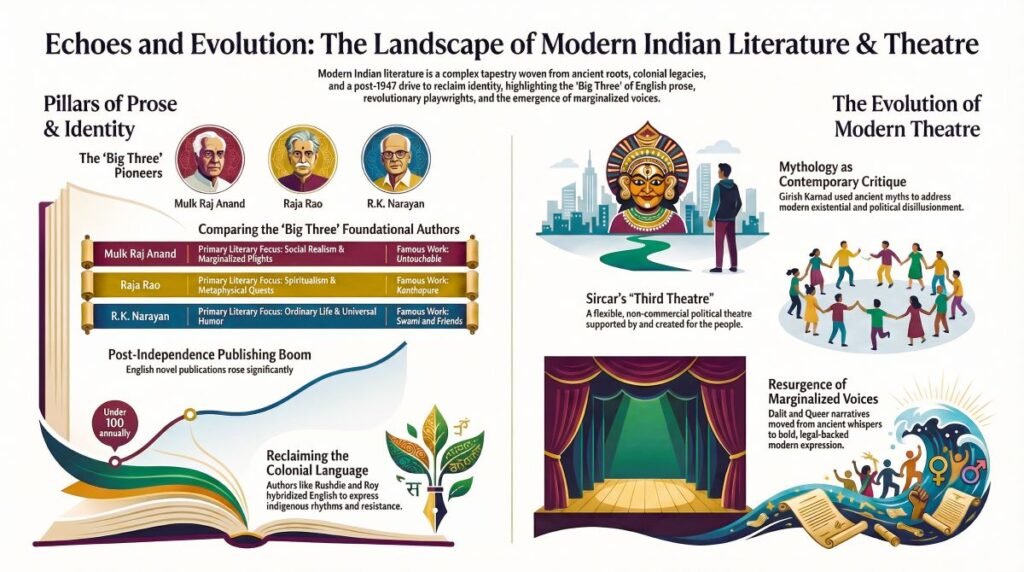

The decades immediately before Indian independence in 1947 saw the emergence of the Indian English novel as a serious literary form. Three writers in particular stand out as the founding fathers of this genre.

R.K. Narayan (1906–2001)

Rasipuram Krishnaswami Narayan is perhaps the most beloved of all Indian English novelists. His greatest achievement was the creation of the fictional South Indian town of Malgudi – a place so vividly realized that it has become part of the shared imaginative landscape of Indian readers everywhere. Beginning with Swami and Friends (1935), Narayan went on to write over a dozen novels set in Malgudi, including The Bachelor of Arts (1937), The English Teacher (1945), The Financial Expert (1952), The Guide (1958), and The Painter of Signs (1976).

Narayan’s prose is deceptively simple – warm, gentle, and shot through with a quiet irony. He wrote about ordinary Indian middle-class life with an empathy and humor that made his work accessible to readers worldwide without ever sacrificing its rootedness in Indian experience. The Guide won the Sahitya Akademi Award and brought Narayan international fame.

Mulk Raj Anand (1905–2004)

While Narayan gave us Malgudi, Mulk Raj Anand gave us a scalding portrait of caste oppression and poverty in colonial India. His first novel, Untouchable (1935), follows a single day in the life of Bakha, a young sweeper boy whose “untouchable” status condemns him to a life of degradation. The novel, which was prefaced by E.M. Forster, was both a literary achievement and a political act – a direct challenge to the caste system and to colonial indifference.

Anand’s subsequent novels – Coolie (1936), Two Leaves and a Bud (1937), and the Lalu trilogy beginning with The Village (1939) – continued his examination of India’s oppressed classes with passionate intensity. He was a committed socialist and humanist, and his work remains essential reading for anyone seeking to understand the social reality of colonial India.

Raja Rao (1908–2006)

Raja Rao is the most philosophically ambitious of the three founding novelists. His debut novel, Kanthapura (1938), tells the story of a South Indian village’s participation in Gandhi’s non-cooperation movement. What makes the novel extraordinary is Rao’s use of language – he bends English syntax, rhythm, and cadence to approximate the oral storytelling traditions of Kannada and Sanskrit, creating a prose style that feels genuinely new.

In the foreword to Kanthapura, Rao famously confronted what he called “the problem of the Indian writer” – the challenge of expressing Indian thought and feeling in an inherited foreign language. His solution was not to abandon English but to transform it from within. His later masterpiece, The Serpent and the Rope (1960), is a dense, philosophical novel that engages with Vedanta philosophy and remains one of the most intellectually demanding works in the Indian English canon.

#4. Post-Independence Literature: 1947 to the 1980s

A New Nation, New Voices: Indian independence in August 1947 was a moment of extraordinary historical significance – and also of great trauma. The Partition of British India into the new nations of India and Pakistan caused one of the largest forced migrations in human history, with millions displaced and hundreds of thousands killed in communal violence. This catastrophic event left an indelible mark on Indian literature in all languages, including English.

- Santha Rama Rau (1923–2009) wrote her autobiographical account Home to India (1945) and later Remember the House (1956), capturing the experience of educated Indian women navigating the transition from colonialism to independence with intelligence and grace.

- Bhabani Bhattacharya (1906–1988) wrote novels that dealt directly with the tragedies of modern India – the Bengal Famine of 1943 in So Many Hungers! (1947) and Partition in Shadow from Ladakh (1966). His work is notable for its social conscience and its humane compassion.

- Manohar Malgonkar (1913–2010) wrote historical fiction and adventure novels – Distant Drum (1960), Combat of Shadows (1962), and The Princes (1963) – that explored the transition from colonial to independent India from the perspective of soldiers, princes, and men of action.

- Kamala Das (1934–2009), though she also wrote in Malayalam under the name Madhavikutty, produced in English one of the most confessional and sensually charged bodies of poetry in the language. Her autobiography, My Story (1976), and her poetry collection Summer in Calcutta (1965) broke every social convention of the time – speaking openly about female desire, marital unhappiness, and the search for identity. She remains one of the most important voices in Indian English poetry.

- A.K. Ramanujan (1929–1993) was a poet, scholar, and translator who moved between English, Kannada, and Tamil with extraordinary ease. His poetry collections – The Striders (1966), Relations (1971), and Second Sight (1986) – are among the finest in the Indian English tradition, marked by a classical precision and a deep engagement with Indian myth and family memory.

#5. The Rushdie Revolution: 1981 and Its Aftermath

The Midnight’s Children Moment: If there is one book that divides the history of Indian English literature into a before and an after, it is Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, published in 1981. This novel – the story of Saleem Sinai, born at the exact midnight moment of Indian independence, whose life becomes mystically entwined with the fate of the new nation – was a literary thunderclap. It won the Booker Prize in 1981 and later the “Booker of Bookers” in 1993, awarded to the best novel to have won the prize in its first 25 years.

What Rushdie did in Midnight’s Children was to apply the techniques of Latin American magical realism – particularly the influence of Gabriel García Márquez – to the Indian experience, blending history and myth, the political and the personal, the sublime and the grotesque. He also forged a new literary language – an English saturated with Hindustani phrases, Indian rhythms, and South Asian modes of storytelling. This language felt simultaneously rooted and cosmopolitan, local and global.

Midnight’s Children gave permission to a whole generation of writers to be both Indian and experimental, both local and international. Its influence on Indian English literature is incalculable.

Rushdie’s subsequent novels – Shame (1983), The Satanic Verses (1988), The Moor’s Last Sigh (1995), and The Ground Beneath Her Feet (1999) – cemented his reputation as one of the most important writers of the late 20th century, even as The Satanic Verses embroiled him in the famous fatwa controversy that forced him into hiding for nearly a decade.

#6. The 1980s and 1990s: A Literary Renaissance

The Diaspora Voice Emerges: The decades following Midnight’s Children saw an explosion of Indian writing in English, both within India and in the growing diaspora. Publishers in London and New York began paying serious attention to Indian authors, and the Booker Prize became a kind of barometer of Indian literary achievement.

- Vikram Seth (b. 1952) demonstrated the extraordinary range possible within Indian English literature. His verse novel The Golden Gate (1986) – an entire novel written in the sonnets of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, set in San Francisco – was a tour de force of technical virtuosity. He then produced A Suitable Boy (1993), at nearly 1,500 pages one of the longest novels ever published in English, a richly detailed portrait of post-Partition India centered on one mother’s search for a suitable husband for her daughter. Its sequel, A Suitable Girl (2017), appeared more than two decades later.

- Amitav Ghosh (b. 1956) emerged as one of the most intellectually ambitious and geographically wide-ranging Indian novelists. The Shadow Lines (1988) explored memory, nationalism, and the violence of Partition and communal riots through a non-linear narrative that has become a landmark of postcolonial fiction. The Calcutta Chromosome (1995) invented a new mode of historical science fiction. His Ibis Trilogy – Sea of Poppies (2008), River of Smoke (2011), and Flood of Fire (2015) – is a sweeping, meticulously researched historical epic set during the Opium Wars. His non-fiction work, especially The Great Derangement (2016) on climate change and culture, has also been hugely influential.

- Vikram Chandra (b. 1961) produced in Sacred Games (2006) one of the great urban novels in any language – a labyrinthine crime epic set in Mumbai that is also a profound meditation on Indian history, mythology, and modernity.

- Upamanyu Chatterjee (b. 1959) wrote with savage wit about the Indian civil service in English, August: An Indian Story (1988), one of the funniest and most searingly honest novels about post-independence disillusionment.

The Booker Prize and Arundhati Roy

No event better illustrates the arrival of Indian English literature on the world stage than Arundhati Roy’s debut novel The God of Small Things winning the Booker Prize in 1997. The novel – set in Kerala and telling the story of a Syrian Christian family destroyed by caste prejudice and forbidden love – is written in a prose of such linguistic originality and emotional depth that it became an immediate classic.

Roy’s career after The God of Small Things took a remarkable turn. She largely abandoned fiction for two decades to become one of India’s most prominent political essayists, writing with passionate advocacy on topics including the Narmada Dam displacement, nuclear weapons, corporate power, and the Kashmir conflict. Her essay collections – The Cost of Living (1999), Power Politics (2001), An Ordinary Person’s Guide to Empire (2004) – established her as a major public intellectual. She returned to fiction with The Ministry of Utmost Happiness in 2017, a sprawling, polyphonic novel about contemporary India.

#7. Indian Diaspora Literature: Writing Between Worlds

The South Asian Diaspora Writers: The Indian diaspora – Indians who have settled in the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and other parts of the world – has produced a rich and distinct body of literature. These writers occupy a fascinating in-between space: they write about India from the outside, and about their adopted countries as insiders who are also perpetual outsiders.

- Bharati Mukherjee (1940–2017) was among the earliest and most important diaspora voices. Her novel Jasmine (1989) and story collection The Middleman and Other Stories (1988) – which won the National Book Critics Circle Award – examined the experiences of South Asian immigrants in North America with unflinching honesty, exploring both the violence and the possibility of reinvention in a new world.

- Jhumpa Lahiri (b. 1967) won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 2000 for her debut story collection Interpreter of Maladies (1999). Her work – including the novel The Namesake (2003) and the story collection Unaccustomed Earth (2008) – is characterized by an elegiac precision, a deep attention to the emotional textures of immigrant life, and a mastery of the short story form. More recently, Lahiri has shifted to writing in Italian – a remarkable act of linguistic self-reinvention that has itself become the subject of one of her books, In Other Words (2015).

- Rohinton Mistry (b. 1952) writes from his base in Canada about the Parsi community of Mumbai with extraordinary compassion and Dickensian density of social observation. His novel A Fine Balance (1995) – set during Indira Gandhi’s Emergency period of 1975–77 – is one of the great novels of post-independence India, a heartbreaking account of how ordinary lives are crushed by political violence.

- Kiran Desai (b. 1971) won the Booker Prize in 2006 for The Inheritance of Loss, a novel that moves between the Himalayan foothills of northeast India and New York City, exploring the legacies of colonialism and the experience of illegal immigration with both lyrical beauty and political intelligence. Her mother, Anita Desai (b. 1937), is herself a celebrated novelist – Clear Light of Day (1980), In Custody (1984), and Baumgartner’s Bombay (1988) are among the finest Indian English novels of the 20th century.

#8. Contemporary Indian English Literature: The 21st Century

A New Generation of Writers: The 21st century has seen Indian English literature flourish in extraordinary new directions. A new generation of writers has emerged who are less concerned with questions of colonial legacy and more interested in the textures of contemporary Indian life – urban, digital, increasingly unequal, and fascinatingly complex.

- Aravind Adiga (b. 1974) won the Booker Prize in 2008 with his debut novel The White Tiger, a darkly comic account of a poor villager’s ruthless rise through India’s new economy, narrated in the form of letters to the Chinese Premier. The novel’s unflinching portrait of the dark side of India’s economic growth was controversial but hugely acclaimed.

- Anuradha Roy (b. 1967) has produced a string of beautifully crafted novels – An Atlas of Impossible Longing (2008), The Folded Earth (2011), and Sleeping on Jupiter (2015, winner of the DSC Prize for South Asian Literature) – that explore Indian landscapes, relationships, and histories with lyrical intensity.

- Perumal Murugan (b. 1966), primarily a Tamil-language writer, has had several of his works translated into English to great acclaim – Seasons of the Palm (2004), One Part Woman (2013), and Poonachi: Or the Story of a Black Goat (2016). His case became a cause célèbre in 2015 when right-wing groups pressured him to stop writing following the publication of One Part Woman; his subsequent return to writing was celebrated as a victory for freedom of expression.

- Jerry Pinto (b. 1966) won the Hindu Literary Prize for his novel Em and the Big Hoom (2012), a deeply personal account of living with a mentally ill mother set in working-class Mumbai.

- Mohsin Hamid, though Pakistani rather than Indian, deserves mention here as a voice from the subcontinent whose work – The Reluctant Fundamentalist (2007), How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia (2013), and Exit West (2017) – has been widely read and discussed across South Asia and beyond.

- Chetan Bhagat (b. 1974) represents a genuinely different kind of Indian English literary phenomenon. His debut novel Five Point Someone (2004) and subsequent books – 2 States (2009), Half Girlfriend (2014) – have sold in the tens of millions, making him far and away the bestselling Indian novelist of his generation. Bhagat writes in a deliberately simple, colloquial style aimed at young, first-generation English readers, and while literary critics have often been dismissive, his cultural impact on the reading habits of middle India has been enormous.

Women’s Voices in Contemporary Indian English Literature

The 21st century has been particularly marked by the emergence of powerful women’s voices in Indian English literature, tackling everything from gender violence to queer identity to the politics of the body.

- Manju Kapur (b. 1948) writes about women’s lives in urban North India with nuanced psychological acuity. Difficult Daughters (1998), A Married Woman (2002), and Home (2006) examine the constraints and desires of educated Indian women across generations.

- Shashi Deshpande (b. 1938) has been writing with quiet power about middle-class Indian women for decades – That Long Silence (1988), which won the Sahitya Akademi Award, and A Matter of Time (1996) are especially notable.

- Meena Kandasamy (b. 1984) represents a new kind of radical feminist voice in Indian writing. Her poetry collection Touch (2006) and her novels The Gypsy Goddess (2014) and When I Hit You: Or, A Portrait of the Writer as a Young Wife (2017) confront caste violence and domestic abuse with formal innovation and searing honesty.

#9. Indian English Poetry: A Tradition of Its Own

While Indian English fiction has received the lion’s share of critical attention, Indian English poetry has its own rich and sophisticated tradition deserving of separate acknowledgment.

- Dom Moraes (1938–2004) won the prestigious Hawthornden Prize in 1958 for his collection A Beginning – the first Indian and the youngest writer ever to win the award. A celebrated journalist as well as a poet, Moraes wrote with great formal elegance and a distinctly cosmopolitan sensibility.

- Nissim Ezekiel (1924–2004) is considered the father of Indian English poetry in the modern sense. His collections – including A Time to Change (1952), Sixty Poems (1953), and Latter-Day Psalms (1982) – established a distinctly Indian urban poetry in English, drawing on Bombay’s multicultural life with irony, self-awareness, and wit. His “Very Indian Poems in Indian English” series, which playfully mirrored Indian English speech patterns, became iconic.

- Jayanta Mahapatra (b. 1928) is perhaps the finest poet in the Indian English tradition. His collections – Svayamvara and Other Poems (1971), A Rain of Rites (1976), and Relationship (1980) – are marked by a profound engagement with Odisha’s landscape and the psychological weight of Indian history, written in a language of compressed, sometimes haunting power.

- Eunice de Souza (1940–2017), Sujata Bhatt (b. 1956), and Imtiaz Dharker (b. 1954) have all produced important bodies of work in Indian English poetry, each bringing distinctive thematic and formal concerns to the tradition.

Also read: Timon of Athens by William Shakespeare PPT Download (.pptx)

#10. Indian English Drama: The Overlooked Genre

Indian English literature’s most overlooked genre is perhaps drama. While the Indian English novel and poem have received extensive critical attention, the theatre tradition has been less visible – partly because theatre is a performative art that does not travel as easily in printed form.

- Asif Currimbhoy (1928–1994) is often considered the first significant Indian playwright in English. He wrote over 30 plays, including The Doldrummers (1960), Inquilab (1970), and An Experiment with Truth (1969), which dramatized Gandhi’s life. His work tackled colonial history, class struggle, and religious conflict with theatrical boldness.

- Mahesh Dattani (b. 1958) is the most prominent Indian English playwright of the contemporary era and the first Indian playwright writing in English to receive the Sahitya Akademi Award, for his collected plays in 1998. His work – Final Solutions (1993), Tara (1991), Dance Like a Man (1989), and Bravely Fought the Queen (1991) – tackles gender, sexuality, caste, and communal violence with a theatricality that is both bold and emotionally precise.

- Girish Karnad (1938–2019), though he primarily wrote in Kannada, wrote plays that have been widely translated and performed in English. Tughlaq (1964), Hayavadana (1972), and Naga-Mandala (1990) draw on Indian history and mythology to explore themes of power, identity, and the divided self.

#11. Key Themes in Indian English Literature

Understanding Indian English literature requires familiarity with the recurring themes that run through this diverse body of work. These themes are not merely literary conventions but reflections of the lived experience of a vast, complex nation.

- Colonialism and its Aftermath: The colonial encounter and its psychological, social, and political consequences are present in virtually every major work of Indian English literature, from Anand’s depictions of colonial poverty to Rushdie’s mythologizing of independence to Ghosh’s historical excavations of the Opium War era.

- Partition and Communal Violence: The trauma of the 1947 Partition remains a recurring obsession – in Mistry’s A Fine Balance, in Bhisham Sahni’s Tamas (originally written in Hindi but widely known in English translation), and in dozens of other works. Communal violence between Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs continues to haunt Indian English fiction.

- Caste and Class: From Anand’s Untouchable to Roy’s The God of Small Things to Adiga’s The White Tiger to Kandasamy’s The Gypsy Goddess, caste discrimination and class inequality are central concerns of Indian English literature.

- Identity and Belonging: Questions of who one is – as an Indian, as a member of a religious community, as a member of a caste, as a gendered subject, as a diasporic Indian – run through the entire tradition.

- Language Itself: Perhaps uniquely, Indian English literature is self-conscious about its own medium. The question of what it means to write in English, a formerly colonial language, about Indian experience is explicitly addressed in texts from Raja Rao’s Kanthapura onward.

- Mythology and Modernity: Indian English writers draw extensively on Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, Buddhist, and other mythological and religious traditions – but always in tension with the demands and disruptions of modernity.

#12. Awards, Recognition, and Global Impact

Indian English literature has been recognized with virtually every major literary prize in the English-speaking world.

The Booker Prize has been won by Indian-origin writers on multiple occasions: V.S. Naipaul (1971, though Trinidadian of Indian descent), Salman Rushdie (1981), Arundhati Roy (1997), Kiran Desai (2006), and Aravind Adiga (2008).

- The Sahitya Akademi Award – India’s most prestigious literary honor – has been awarded to numerous Indian English writers.

- The JCB Prize for Literature, established in 2018, has quickly established itself as the premier award for Indian fiction across languages.

- The DSC Prize for South Asian Literature recognizes fiction from the broader South Asian region.

Internationally, Indian English authors have been shortlisted for or won the Pulitzer Prize (Lahiri), the National Book Award (Mukherjee), and numerous other honors.

#13. The Digital Age and the Future of Indian English Literature

The 21st century has brought new forms and new platforms to Indian English literature. Literary journals, blogs, online magazines, and social media platforms have dramatically democratized literary culture, allowing voices that might previously have been excluded from traditional publishing to reach large audiences.

Literary festivals – particularly the Jaipur Literature Festival, which has grown into the largest free literary festival in the world – have become crucial sites for the discovery, discussion, and celebration of Indian writing. Self-publishing and digital publishing have created space for genres – crime fiction, science fiction, fantasy, romance, graphic novels – that the Indian English literary establishment had historically overlooked. Writers like Amish Tripathi (b. 1974), whose Shiva Trilogy has sold over five million copies, represent a new kind of popular mythological fiction that blends ancient Indian narratives with contemporary storytelling techniques. The future of Indian English literature seems bright and unpredictable. New voices continue to emerge from every corner of the subcontinent and the diaspora, writing about experiences and realities that previous generations could not have imagined.

Beyond the Canon: 6 Surprising Takeaways That Redefined Indian Literature

I. The Stories We Thought We Knew

For the curious reader, the history of Indian literature often feels like a static monument-a distant horizon of ancient Sanskrit epics followed by a sudden leap into the post-colonial giants of the twentieth century. Yet, a closer inspection of the archival record reveals a landscape that is far more radical, porous, and inherently political than the traditional canon suggests. The evolution of Indian writing is not merely a chronological sequence of books; it is a series of intellectual “firsts” and acts of profound subversion.These stories represent a continuous effort to reclaim agency against external impositions, shifting the literary focus from exotic myths to empirical realities. From the first traveler to map the “White other” to the reclamation of ancient gender fluidity in the face of Victorian censorship, these narratives challenge the prevailing global order. To understand the modern Indian literary identity, one must look beyond the standard textbooks and explore these six surprising shifts that redefined how India writes itself.

1. The Immigrant Who “Discovered” England: Dean Mahomed

In 1794, Dean Mahomed published The Travels of Dean Mahomed , establishing himself as the first Indian author to write in English. While European travelers had long depicted the East as an “unreal” circus of marble palaces and snake charmers, Mahomed enacted an imperial subversion where the subaltern finally assumes the role of the ethnographer. He performed a “reverse gaze,” mapping out England from the perspective of an Indian immigrant and effectively “discovering” the West for the East.Mahomed did not merely observe; he reduced the colossal, mythical idea of England that lived in the Indian imagination to an empirical reality. By documenting the mundane sights of Cork and London-noting their industrial smells, squalor, and the “hideous troops of beggars”-he stripped away the romanticized veil of the Occident. His contribution was also cultural; he introduced the “shampooing” ( champi ) bath and founded the Hindostani Coffee House in 1810, proving that the subaltern could define the culture of the colonizer.

2. Ancient Fluidity vs. Colonial Chains: The Queer Literary Thread

Indian literature possesses a long-standing relationship with gender fluidity that predates modern Western discourse by centuries. Ancient Puranic works like the Padma Purana and Markandeya Purana depict gender transformations, such as Arjuna becoming Arjuni, while the medical treatise Sushruta Samhita recognized homosexuality and transgenderism as empirical realities. Central to this lore is the concept of Ardhanareeshwara -a term derived from ardha (half), naree (woman), and eshwara (lord)-representing the divine union of masculine and feminine energies.This ancient “sunlight” of fluidity was eventually obscured by the “shadow” of British colonial rule and the imposition of Victorian morals via Section 377 . Same-sex desire was forced into the realm of tragic endings or guarded metaphors, a shift captured in the early 1900s. Today, modern writers like Amruta Patil and Devdutt Pattanaik are unearthing these buried narratives to challenge the rigid, categorical structures inherited from the colonial era.”The words and descriptions left no doubt about what was being alluded to almost like whispered secrets carried on the wind.” – Pandey Bechan Sharma ‘Ugra’ , regarding his book Chocolate .

3. The “Big Three” and the Architecture of Modern Identity

During the 1930s and 1940s, a golden period of Indian Writing in English (IWE) emerged, anchored by three foundational figures who provided the blueprint for a post-colonial identity. Mulk Raj Anand utilized social realism in Untouchable (1935) to grant a global voice to the marginalized, while R.K. Narayan found universality in the particular through the fictional town of Malgudi in Swami and Friends (1935). Raja Rao completed the triad with Kanthapura (1938), bridging the metaphysical with the mundane through a lyrical, meditational style.These authors were not merely storytellers; they were architects of a new synthesis between Indian ethos and English linguistic tradition. Anand’s social protest, Narayan’s regional empathy, and Rao’s Gandhian spiritualism interwove to create a balanced framework for modern identity. By grounding their debut novels in the specific socio-political upheavals of the 1930s, they ensured that Indian sensibilities could thrive and command respect within a global literary framework.

4. Girish Karnad: Using 14th-Century Sultans to Critique the Present

Girish Karnad redefined Indian playwriting in the 1960s by using the distant past as a surgical tool to dissect the contemporary existential crisis. His breakthrough play, Tughlaq (1964), centered on the 14th-century Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq , yet it functioned as a biting allegory of the Nehruvian era . Karnad saw a striking parallel between the medieval king’s ambitious idealism and the national disillusionment that characterized India’s political landscape in the 1960s.Karnad’s methodology was uniquely visceral; he described himself as a “scribe” to an “involuntary rush of dialogues” that brought mythological and historical figures to life. To tackle modern psychological conflicts, he often employed the vibrant folk theater form of Yakshagana and ancient legends found in works like Yayati and Hayavadana . By utilizing these historical masks, Karnad provided a vehicle for political critique that felt both ancient and urgently modern.

5. Tagore’s “Educational Rebellion” and the Global Short Story

While Rabindranath Tagore is often cast as a mystic poet, his most radical legacy lies in a deliberate “educational rebellion” against rigid colonial structures. He founded Shantiniketan in 1901 to promote a holistic learning environment free from conventional classroom constraints. This spirit of subversion extended to his linguistics; Tagore simplified the Bengali language to strip away elite literary norms and make the written word accessible to the common people.Tagore was a pioneer of the short story form, using narratives like Kabuliwala and The Postmaster to explore the nuances of human connection against the backdrop of rural Bengal. His humanism was particularly revolutionary in his portrayal of women who defied societal expectations. In works like The Home and the World , he presented female characters navigating the complex intersection of personal desire and political duty, challenging the traditional domestic roles assigned to them.

6. Badal Sircar and the “Third Theatre” Revolution

In the late twentieth century, Badal Sircar initiated a radical departure from commercial drama through his concept of the Third Theatre . He envisioned a “flexible theatre” that was rigorously non-commercial and political-a theater created by the people, for the people. This model relied on a unique four-way flow of influence: actor-to-actor, audience-to-actor, actor-to-audience, and audience-to-audience, effectively dissolving the barrier between the performer and the spectator.Sircar’s play Evam Indrajit (1963) is credited with introducing “existential angst” to the Indian stage with a sense of immediate, visceral reality. By removing the physical and financial constraints of the traditional proscenium theater, Sircar forced his audience to confront the difficult truths of their own lives and social responsibilities. His work sought the true liberation of the individual, transforming the stage into a site of active social change rather than mere entertainment.

The Power of the Reclaimed Narrative

The trajectory of Indian literature is a testament to the enduring power of reclaiming agency through the written word. From Dean Mahomed’s mapping of the West to Sircar’s street-level activism, these writers transformed literature into a site of resistance and self-definition. They proved that the Indian narrative is not a fixed monument but a fluid, living dialogue that continuously subverts external impositions to find its own authentic voice.The 2018 Supreme Court decision to decriminalize homosexuality has served as a modern catalyst, allowing a new chorus of writers to reclaim narratives that were silenced for over a century. This legal victory is not just a policy change but a literary liberation, signaling a return to the fluidity of our ancient past. As we look toward the next century of writing, one must wonder: which “whispered secrets” of our current era will be reclaimed as the groundbreaking literature of the future?

Conclusion: A Literature of Extraordinary Vitality

The history of Indian English literature is, at one level, the history of a remarkable adaptation and appropriation – the taking of a colonial language and making it do entirely new kinds of work. It is a history marked by great individual talent, by profound political engagement, and by a restless formal creativity. From Henry Derozio’s early Romantic verse to Rushdie’s carnivalesque modernism, from R.K. Narayan’s gentle realism to Arundhati Roy’s lyrical fury, from Tagore’s spiritual poetry to Jhumpa Lahiri’s exquisitely calibrated short stories, Indian English literature represents one of the richest literary traditions of the modern world. It is a tradition that refuses to stand still – that is always in conversation with both its Indian roots and its global context, always wrestling with the languages, forms, and ideas it has inherited, always pushing toward new ways of telling the truth about human experience. For anyone who loves literature, there has never been a better time to explore what Indian writers in English have made of their extraordinary and complicated world.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: When did Indian English literature begin?

Most scholars trace the formal beginning of Indian English literature to the early 19th century, with poets like Henry Derozio writing in the 1820s and 1830s. However, Rabindranath Tagore’s English translations of the early 20th century gave Indian writing its first major international recognition.

Q: Who is considered the father of Indian English novel?

The three pioneers of the Indian English novel are R.K. Narayan, Mulk Raj Anand, and Raja Rao, whose works in the 1930s first established the form. If one name must be chosen, R.K. Narayan is most frequently cited as the foundational figure, due to the longevity and influence of his Malgudi novels.

Q: What is the most famous work of Indian English literature?

Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children (1981) and Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things (1997) are the two most celebrated and internationally recognized works. Both won the Booker Prize.

Q: Which Indian English writer won the Nobel Prize?

Rabindranath Tagore won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913 – primarily for Gitanjali in its English translation. Though his original work was in Bengali, this remains the Nobel Prize most closely associated with Indian literature. V.S. Naipaul, born in Trinidad to Indian parents, won the Nobel Prize in 2001.

Q: What are the main themes in Indian English literature?

The major themes include colonialism and postcolonialism, Partition and communal violence, caste and class inequality, identity and belonging, diaspora experience, the role of women, mythology and modernity, and the politics of language itself.

Q: What are the best Indian English novels to start with?

For readers new to Indian English literature, a good starting list might include: The Guide by R.K. Narayan, Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie, The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy, A Fine Balance by Rohinton Mistry, The Shadow Lines by Amitav Ghosh, and Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri.